Fascinating study, another classic, which shows SABR at it's best. More useful tidbits about first understanding and then controlling the single most important element in the game. "The Count".

from SABR.org

Study of ‘The Count’ Yields Fascinating Data

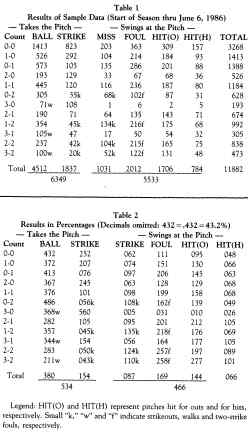

---The results support many homilies about the benefits that a pitcherenjoys by staying ahead of the hitter - and also show that batters hit36 points higher with runners aboard than with the sacks empty.

In analyzing the results, certain statistics seem to stand out especially strongly. The following comments relate to some of the most interesting of these.MISSED SWINGS. Perhaps the most striking statistic is the extraordinarily low percentage of swung-on pitches which are missed completely. Fewer than one out of every five swings is missed completely; about 45% of swings produce either a hit or an out, and the balance (3 6%) are fouled off. One marvels at the skills of major league batters to make contact so consistently and also at those pitchers who are able to strike out ten or more of these batters in a game.TAKEN PITCHES. Further testament to the extra-ordinary "eye" of the major league batter is his apparent ability to discern a good pitch from a bad one. While there is no way to record the number of bad pitches swung at, the statistics do show that on those occasions when the batter chooses NOT to swing, he is right (i.e., the pitch is called a ball) about 71% of the time. If this is true of the AVERAGE player, imagine what the skill of a Ted Williams must have been!CALLED VS. SWINGING STRIKEOUTS. At the earliest stages of almost every player's introduction to the game, it is axiomatic that he will be told to "never take a called third strike"; yet more than 28% of the strikeouts recorded in the sample were called third strikes. This is a statistic which is hard to accept at face value (especially since only 29% of taken pitches are called strikes, regardless of the count), although every subsample confirms this result. The implication would be that a batter's ability to "protect the plate" does not improve much when he has two strikes on him.IN FACT, that appears to be the case. The percentage of pitches fouled off of pitches swung at remains consistently between 33% and 40% for all counts on the batter. And the highest percentage - 40% - is for the 0-1 pitch.Despite the statistics attesting to the high ability of batters to discern good pitches from bad ones, it would appear that many marginal pitches are being let go and are resulting in called strikeouts. This may be a prime example of the "umpire factor" at work - perhaps the umpire feels a need to punish the batter for not swinging at a pitch close enough to the strike zone when he has two strikes on him, thus giving the pitcher the benefit of the doubt.THE 0-2 PITCH. The aforementioned inability of batters to improve their ability to protect the plate with two strikes on them makes questionable the cherished notion of using the 0-2 pitch as a "waste pitch." And the statistics bear out this questioning of the "book." In those instances with an 0-2 count when the pitcher put the ball close enough to the strike zone to compel the batter to swing at it, the batter struck out 24% of the time! This compares quite favorably with the overall 19% swing-and-miss rate for all counts.In addition, on those occasions when the batter watched the 0-2 pitch go by, more than 10% were called third strikes. Considering that some portion of these tosses were "waste pitches" anyway, there seems to be reason to believe that a pitch somewhere near the strike zone has a reasonably good chance to be given the benefit of the doubt by the umpire. In any event, this area definitely deserves more detailed research.THE 3-0 PITCH. The fact that almost 60% of all 3-0 pitches are taken for a called strike should probably not be surprising. What WAS interesting, however, was the wide difference observed in the percentage of batters swinging at the 3-0 pitch (14 of 193, about 7.3%) compared to the Palmer study of all World Series games played between 1974 and 1982 (66 of 336, or 19.6%)! Can it be that World Series managers are likely to give a green light to a batter on a 3-0 pitch almost one out of every five times, when they do so about one time in 14 during the regular season? Since both studies eliminated intentional walks from the data base, there is no reason to assume a statistical bias one way or the other.Moreover, the divergence of the data does not end merely with the frequency of swinging at the pitch; the results of those swings are significantly different as well. Palmer reported that of the 66 World Series players swinging at the 3-0 pitch, 34 missed it completely! This is a staggering 51.5% miss rate, higher by far than any sample at any count under any condition. In contrast, the 14 swings in this study produced only one complete miss, six foul balls and seven balls put into play.While both samples are admittedly too small to draw any conclusions with confidence, the results of the current study are at least compatible with what has been observed for batters in general. This extraordinarily wide divergence of observed behavior in the regular season vs. World Series play certainly deserves closer scrutiny.BASES EMPTY VS. RUNNERS ON BASE. While it should be expected that significantly different patterns exist when there are runners on base and when the bases are empty, the extent of those differences was surprisingly large. Batting averages with runners on base were .036 higher than with bases empty (.285 vs .249), and the strikeout rate was only 14.7% compared to a bases-empty rate of 16.3%It is not difficult to postulate reasons why this should be so. With bases empty almost all pitchers throw from a full windup (a few relievers, such as Kent Tekulve and Jim Winn, throw exclusively from the stretch), which should produce a marginally faster pitch to hit. Also, since a hit is relatively more dangerous than a walk with men on base, a catcher is more likely to call for curves, knucklers, etc., which are more likely to be outside the strike zone but are also less likely to become base hits; he is not as apt to ask the pitcher to "challenge" the hitter. Unfortunately, this often leads to the pitcher falling behind in the count, which, combined with the stretch position, creates a situation generally more favorable for the hitter. And as the data show, the batters tend to respond with a vengeance.

from Hardball Times:

The Importance Of Strike One (and Two, and Three…), Part 2

Now there are also additional benefits to throwing first-pitch strikes, other than just those bare results. Strikes also end plate appearances early; therefore preserving a pitcher's freshness and allowing him to face more hitters. Johnny Sain, the legendary pitching coach who has left dozens if not hundreds of disciples throughout baseball, said that the best pitch in baseball was the one-pitch out. Certainly the ideal result for a pitcher isn't the strikeout, but the one-pitch out. Even putting that to one side, though, surely the notion that strike one (no matter if it's put into play, swinging, called, foul, or what have you) is worth two runs a game is enough to encourage pitchers to throw first strikes more often? (Pitchers threw first-pitch strikes 57% of the time in 2003). Now if that perfectly average pitcher threw first-pitch strikes 80% of the time instead of 57%, his ERA would decrease by about 0.64. If every pitcher on a team did it, it would save that team about 100 runs a year, or ten wins, turning average teams into pennant contenders.

Now pitching coaches, and other baseball people, will often tell you that 1-1 is the most important count for a pitcher, because of the massive difference between 2-1 and 1-2. Mike Marshall, in a discussion with Steve ("CrashCourse") of NetShrine, recently said that

"The highest batting average hitters achieve is in their one pitch at bats. Therefore, while strike one is very good, it has to be a pitch that does not allow hits. The key to pitching is one ball two strikes rather than two balls one strike. The first pitch is important, but the next two pitches are just as important."

Likewise, Greg Maddux considers the 1-1 pitch the most important pitch in baseball, because 1-2 and 2-1 are "different worlds". On the other hand, Reds pitching coach Don Gullett and Giants manager Felipe Alou - amongst others - say that the first-pitch strike is the most important.

There is another way to look at the de-emphasis of the 0-0 strike and the emphasis on 1-1 and later counts that shows the wisdom of throwing early strikes. Starting pitchers in particular need quick at-bats. Starters who work hitters into deep counts do have more success in reducing batting averages as Mike Marshall points out. However, pitchers cannot consistently throw five, six, or seven pitches in an at-bat and still be successful, as Marshall himself points out in his online book, Coaching Pitchers:

Free Book

1. Pitchers should throw all pitches for 66.7% strikes.

2. Pitchers should end 75% of at bats within three pitches.

3. Pitchers should end 100% of at bats within five pitches.

In order to end at-bats quickly, pitchers must maximize the number of strikes they throw early in the count, on the first three pitches. The base hits on early strikes - and they are going to happen - are a pitcher's occupational hazard. Pitchers shouldn't let them get in the way of pressuring hitters.

0-0 is the predominant count in baseball. The first strike is the soul of every pitcher's success, and pitchers who don't throw first-pitch strikes get killed. Consistently, even the most hittable pitchers in the majors give up base hits on fewer than 10% of their first-pitch strikes. Certainly, the old saw that the pitcher's most important pitch is a strike, rings true. But another popular piece of myth, that the 1-1 count is the big one, should probably be put out to pasture.

'via Blog this'

No comments:

Post a Comment