This is what being a willing accomplice to fear can lead to. Learned Helplessness.

The Baby Elephant Syndrome

There is a story about elephants and their owners in Africa. Look at an adult elephant; it can easily uproot huge trees with its trunk; it can knock down a h...

| |||||||

There is a story about elephants and their owners in Africa. Look at an adult elephant; it can easily uproot huge trees with its trunk; it can knock down a house without much trouble.

When an elephant living in captivity is still a baby, it is tied to a tree with a strong rope or a chain every night. Because it is the nature of elephants to roam free, the baby elephant instinctively tries with all its might to break the rope. But it isn't yet strong enough to do so. Realizing its efforts are of no use, it finally gives up and stops struggling. The baby elephant tries and fails many times, it will never try again for the rest of its life.

Later, when the elephant is fully grown, it can be tied to a small tree with a thin rope. It could then easily free itself by uprooting the tree or breaking the rope. But because its mind has been conditioned by its prior experiences, it doesn't make the slightest attempt to break free. The powerfully gigantic elephant has limited its present abilities by the limitations of the past—-hence, the Baby Elephant Syndrome.

Human beings are exactly like the elephant except for one thing—We can CHOOSE not to accept the false boundaries and limitations created by the past…

" Don't let your past dictate who you are, but let it be part of who you become."

- Anonymous

The Elephant Syndrome: Learned Helplessness

The concept of learned helplessness should resonate clearly for most of you because the evidence of its existence is so easily seen in...

When an elephant living in captivity is still a baby, it is tied to a tree with a strong rope or a chain every night. Because it is the nature of elephants to roam free, the baby elephant instinctively tries with all its might to break the rope. But it isn't yet strong enough to do so. Realizing its efforts are of no use, it finally gives up and stops struggling. The baby elephant tries and fails many times, it will never try again for the rest of its life.

Later, when the elephant is fully grown, it can be tied to a small tree with a thin rope. It could then easily free itself by uprooting the tree or breaking the rope. But because its mind has been conditioned by its prior experiences, it doesn't make the slightest attempt to break free. The powerfully gigantic elephant has limited its present abilities by the limitations of the past—-hence, the Baby Elephant Syndrome.

Human beings are exactly like the elephant except for one thing—We can CHOOSE not to accept the false boundaries and limitations created by the past…

" Don't let your past dictate who you are, but let it be part of who you become."

- Anonymous

The Elephant Syndrome: Learned Helplessness

The concept of learned helplessness should resonate clearly for most of you because the evidence of its existence is so easily seen in...

| |||||||

THE ELEPHANT SYNDROME: LEARNED HELPLESSNESS

The concept of learned helplessness should resonate clearly for most of you because the evidence of its existence is so easily seen in most any organization or home environment. Helplessness is any condition where a desired escape or change is impossible. When we speak of learned helplessness, we are referring to a state in which a person perceives (incorrectly) that there are no opportunities for escape or means by which they can effect a change.

Most of you have probably seen television documentaries or read stories about how elephant trainers control their huge wild animals in captivity. A full-grown male African Elephant can measure 7 ½ meters in length and weigh 6 tons or more. But a baby elephant is quite manageable in size and strength and is easily restrained to a small area with one end of a chain fastened to its leg and the other to a good sized tree. The elephant soon learns that escape is impossible. However, this inescapable condition is soon outgrown. The questions then becomes, why doesn't the animal escape? Because it has over-learned that the specific act of escape from the restraint is impossible. Not only this, but the animal submits to the overall authority of its master because its submission to the restraint is generalized to other areas. This intelligent animal learns at an early age that it must submit to the will of its master. It is quite amazing to see these mammoth giants being guided around by a puny rope or ridden like a pony on steroids. But this is only possible because of the conditioning that the animal experienced early in its life. In essence, the elephant has learned that it is helpless, that it can not escape and that it must submit to the will of its master.

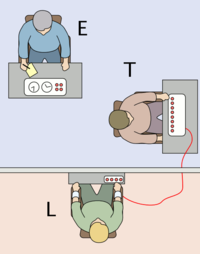

Dr. Martin Seligman, Fox Leadership Professor of Psychology at the University of Pennsylvania, I is widely accepted as the father of learned helplessness. His work on learned helplessness began in the animal laboratory of Richard Solomon at the University of Pennsylvania in the mid 1960's. Solomon was studying what is called avoidance behavior. Avoidance behaviors are established when subjects learn that a warning stimulus or signal (in this case a light) is followed by an averse stimulus (in this case a mild shock). These researchers were studying the ability of dogs to learn the warning stimulus and avoid the averse stimulus. In essence, they were conditioning (training) dogs to expect a shock if they did not react appropriately to a warning light.

What they found was that dogs could and would act (be motivated) by their own expectations that an averse stimulus (shock) would result if they did not act. However, these results were logically problematic for the researchers to explain. If what they were seeing was simply a tendency to be motivated by the absence of a shock, then wouldn't these animals be equally as motivated to engage in all behaviors (eating, grooming, barking and pooping) that were not followed by shocks? This mystery led to further experimentation in order to determine the conditions under which dogs would develop such expectations. Clearly, eating and other normal animal behaviors were not motivated by a desire to avoid any clear averse stimuli.

In 1967, Overmier and Seligman first began a set of experiments designed to discover what conditions were required for the development of this avoidance behavior. Dogs experienced one of two laboratory conditions. The animals were first treated with either escapable shocks ( shocks that could be terminated by a response) or inescapable shocks. These same dogs were then tested in a different apparatus (a different setting with a different averse stimulus). What they found was that the animals that had received the escapable shocks first learned normally in later conditions. However, animals that had initially received the same shocks but under inescapable conditions failed to learn later. In addition, future studies showed that an experience of escapable shock "immunized" the animals so that a later exposure to inescapable shock was without effect on later learning. Overmier and Seligman had made an important discovery, but they had yet to come up with a viable explanation for this behavioral phenomenon.

Although there were many well developed theories that offered insights into the behavioral contingency that Seligman and Overmier had discovered, none of them explained the phenomenon adequately. The researchers knew that the animals that experienced inescapable shocks were learning that their responses to the shock and the termination of the shock condition were independent of one another. The realization that these two factors (shock and escape response) were independent of one another meant that, like the giant elephants, the dogs did not expect that any attempt to escape would succeed. Given this learned condition, the animals' escape response discontinued and they lay passively while receiving the mild shocks. This phenomenon became known as learned helplessness.

The findings of this animal research apply reasonably to our experience as humans. We know that initial failures (like an inability to escape shocks) can have a powerful influence over our belief that further efforts will result in different (and better) results. Seligman and others went on to perform experiments with humans. What they found was that the same consequences appeared in people with animals, but the effects of helplessness were moderated by the person's ability to rationalize what was happening. Since animals have limited rational capabilities, it stood to reason that human would react to the induction of helplessness conditions differentially, depending upon how they perceived the circumstances.

Seligman explained that learning helplessness in humans is modified by their explanatory style. A person's explanatory style is what influences their "self-talk" or their explanations for what they experience (the causes of our successes and failures, escape or inability to escape). Seligman found that people with optimistic explanatory style were far more resilient toward conditions of learned helplessness. Unfortunately, not every person has an optimistic explanatory style.

===

The concept of learned helplessness should resonate clearly for most of you because the evidence of its existence is so easily seen in most any organization or home environment. Helplessness is any condition where a desired escape or change is impossible. When we speak of learned helplessness, we are referring to a state in which a person perceives (incorrectly) that there are no opportunities for escape or means by which they can effect a change.

Most of you have probably seen television documentaries or read stories about how elephant trainers control their huge wild animals in captivity. A full-grown male African Elephant can measure 7 ½ meters in length and weigh 6 tons or more. But a baby elephant is quite manageable in size and strength and is easily restrained to a small area with one end of a chain fastened to its leg and the other to a good sized tree. The elephant soon learns that escape is impossible. However, this inescapable condition is soon outgrown. The questions then becomes, why doesn't the animal escape? Because it has over-learned that the specific act of escape from the restraint is impossible. Not only this, but the animal submits to the overall authority of its master because its submission to the restraint is generalized to other areas. This intelligent animal learns at an early age that it must submit to the will of its master. It is quite amazing to see these mammoth giants being guided around by a puny rope or ridden like a pony on steroids. But this is only possible because of the conditioning that the animal experienced early in its life. In essence, the elephant has learned that it is helpless, that it can not escape and that it must submit to the will of its master.

Dr. Martin Seligman, Fox Leadership Professor of Psychology at the University of Pennsylvania, I is widely accepted as the father of learned helplessness. His work on learned helplessness began in the animal laboratory of Richard Solomon at the University of Pennsylvania in the mid 1960's. Solomon was studying what is called avoidance behavior. Avoidance behaviors are established when subjects learn that a warning stimulus or signal (in this case a light) is followed by an averse stimulus (in this case a mild shock). These researchers were studying the ability of dogs to learn the warning stimulus and avoid the averse stimulus. In essence, they were conditioning (training) dogs to expect a shock if they did not react appropriately to a warning light.

What they found was that dogs could and would act (be motivated) by their own expectations that an averse stimulus (shock) would result if they did not act. However, these results were logically problematic for the researchers to explain. If what they were seeing was simply a tendency to be motivated by the absence of a shock, then wouldn't these animals be equally as motivated to engage in all behaviors (eating, grooming, barking and pooping) that were not followed by shocks? This mystery led to further experimentation in order to determine the conditions under which dogs would develop such expectations. Clearly, eating and other normal animal behaviors were not motivated by a desire to avoid any clear averse stimuli.

In 1967, Overmier and Seligman first began a set of experiments designed to discover what conditions were required for the development of this avoidance behavior. Dogs experienced one of two laboratory conditions. The animals were first treated with either escapable shocks ( shocks that could be terminated by a response) or inescapable shocks. These same dogs were then tested in a different apparatus (a different setting with a different averse stimulus). What they found was that the animals that had received the escapable shocks first learned normally in later conditions. However, animals that had initially received the same shocks but under inescapable conditions failed to learn later. In addition, future studies showed that an experience of escapable shock "immunized" the animals so that a later exposure to inescapable shock was without effect on later learning. Overmier and Seligman had made an important discovery, but they had yet to come up with a viable explanation for this behavioral phenomenon.

Although there were many well developed theories that offered insights into the behavioral contingency that Seligman and Overmier had discovered, none of them explained the phenomenon adequately. The researchers knew that the animals that experienced inescapable shocks were learning that their responses to the shock and the termination of the shock condition were independent of one another. The realization that these two factors (shock and escape response) were independent of one another meant that, like the giant elephants, the dogs did not expect that any attempt to escape would succeed. Given this learned condition, the animals' escape response discontinued and they lay passively while receiving the mild shocks. This phenomenon became known as learned helplessness.

The findings of this animal research apply reasonably to our experience as humans. We know that initial failures (like an inability to escape shocks) can have a powerful influence over our belief that further efforts will result in different (and better) results. Seligman and others went on to perform experiments with humans. What they found was that the same consequences appeared in people with animals, but the effects of helplessness were moderated by the person's ability to rationalize what was happening. Since animals have limited rational capabilities, it stood to reason that human would react to the induction of helplessness conditions differentially, depending upon how they perceived the circumstances.

Seligman explained that learning helplessness in humans is modified by their explanatory style. A person's explanatory style is what influences their "self-talk" or their explanations for what they experience (the causes of our successes and failures, escape or inability to escape). Seligman found that people with optimistic explanatory style were far more resilient toward conditions of learned helplessness. Unfortunately, not every person has an optimistic explanatory style.

===

Milgram experiment - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Milgram experiment on obedience to authority figures was a series of social psychology experiments conducted by Yale University psychologist Stanl...

Preview by Yahoo

The concept of learned helplessness should resonate clearly for most of you because the evidence of its existence is so easily seen in most any organization or home environment. Helplessness is any condition where a desired escape or change is impossible. When we speak of learned helplessness, we are referring to a state in which a person perceives (incorrectly) that there are no opportunities for escape or means by which they can effect a change.

The concept of learned helplessness should resonate clearly for most of you because the evidence of its existence is so easily seen in most any organization or home environment. Helplessness is any condition where a desired escape or change is impossible. When we speak of learned helplessness, we are referring to a state in which a person perceives (incorrectly) that there are no opportunities for escape or means by which they can effect a change.

Most of you have probably seen television documentaries or read stories about how elephant trainers control their huge wild animals in captivity. A full-grown male African Elephant can measure 7 ½ meters in length and weigh 6 tons or more. But a baby elephant is quite manageable in size and strength and is easily restrained to a small area with one end of a chain fastened to its leg and the other to a good sized tree. The elephant soon learns that escape is impossible. However, this inescapable condition is soon outgrown. The questions then becomes, why doesn't the animal escape? Because it has over-learned that the specific act of escape from the restraint is impossible. Not only this, but the animal submits to the overall authority of its master because its submission to the restraint is generalized to other areas. This intelligent animal learns at an early age that it must submit to the will of its master. It is quite amazing to see these mammoth giants being guided around by a puny rope or ridden like a pony on steroids. But this is only possible because of the conditioning that the animal experienced early in its life. In essence, the elephant has learned that it is helpless, that it can not escape and that it must submit to the will of its master.

Dr. Martin Seligman, Fox Leadership Professor of Psychology at the University of Pennsylvania, I is widely accepted as the father of learned helplessness. His work on learned helplessness began in the animal laboratory of Richard Solomon at the University of Pennsylvania in the mid 1960's. Solomon was studying what is called avoidance behavior. Avoidance behaviors are established when subjects learn that a warning stimulus or signal (in this case a light) is followed by an averse stimulus (in this case a mild shock). These researchers were studying the ability of dogs to learn the warning stimulus and avoid the averse stimulus. In essence, they were conditioning (training) dogs to expect a shock if they did not react appropriately to a warning light.

What they found was that dogs could and would act (be motivated) by their own expectations that an averse stimulus (shock) would result if they did not act. However, these results were logically problematic for the researchers to explain. If what they were seeing was simply a tendency to be motivated by the absence of a shock, then wouldn't these animals be equally as motivated to engage in all behaviors (eating, grooming, barking and pooping) that were not followed by shocks? This mystery led to further experimentation in order to determine the conditions under which dogs would develop such expectations. Clearly, eating and other normal animal behaviors were not motivated by a desire to avoid any clear averse stimuli.

In 1967, Overmier and Seligman first began a set of experiments designed to discover what conditions were required for the development of this avoidance behavior. Dogs experienced one of two laboratory conditions. The animals were first treated with either escapable shocks ( shocks that could be terminated by a response) or inescapable shocks. These same dogs were then tested in a different apparatus (a different setting with a different averse stimulus). What they found was that the animals that had received the escapable shocks first learned normally in later conditions. However, animals that had initially received the same shocks but under inescapable conditions failed to learn later. In addition, future studies showed that an experience of escapable shock "immunized" the animals so that a later exposure to inescapable shock was without effect on later learning. Overmier and Seligman had made an important discovery, but they had yet to come up with a viable explanation for this behavioral phenomenon.

Although there were many well developed theories that offered insights into the behavioral contingency that Seligman and Overmier had discovered, none of them explained the phenomenon adequately. The researchers knew that the animals that experienced inescapable shocks were learning that their responses to the shock and the termination of the shock condition were independent of one another. The realization that these two factors (shock and escape response) were independent of one another meant that, like the giant elephants, the dogs did not expect that any attempt to escape would succeed. Given this learned condition, the animals' escape response discontinued and they lay passively while receiving the mild shocks. This phenomenon became known as learned helplessness.

The findings of this animal research apply reasonably to our experience as humans. We know that initial failures (like an inability to escape shocks) can have a powerful influence over our belief that further efforts will result in different (and better) results. Seligman and others went on to perform experiments with humans. What they found was that the same consequences appeared in people with animals, but the effects of helplessness were moderated by the person's ability to rationalize what was happening. Since animals have limited rational capabilities, it stood to reason that human would react to the induction of helplessness conditions differentially, depending upon how they perceived the circumstances.

Seligman explained that learning helplessness in humans is modified by their explanatory style. A person's explanatory style is what influences their "self-talk" or their explanations for what they experience (the causes of our successes and failures, escape or inability to escape). Seligman found that people with optimistic explanatory style were far more resilient toward conditions of learned helplessness. Unfortunately, not every person has an optimistic explanatory style.

===

Milgram experiment - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Milgram experiment on obedience to authority figures was a series of social psychology experiments conducted by Yale University psychologist Stanl...

| |||||||

Preview by Yahoo

| |||||||

Results

Before conducting the experiment, Milgram polled fourteen Yale University senior-year psychology majors to predict the behavior of 100 hypothetical teachers. All of the poll respondents believed that only a very small fraction of teachers (the range was from zero to 3 out of 100, with an average of 1.2) would be prepared to inflict the maximum voltage. Milgram also informally polled his colleagues and found that they, too, believed very few subjects would progress beyond a very strong shock.[1] Milgram also polled forty psychiatrists from a medical school, and they believed that by the tenth shock, when the victim demands to be free, most subjects would stop the experiment. They predicted that by the 300-volt shock, when the victim refuses to answer, only 3.73 percent of the subjects would still continue and, they believed that "only a little over one-tenth of one percent of the subjects would administer the highest shock on the board."[7]

In Milgram's first set of experiments, 65 percent (26 of 40)[1] of experiment participants administered the experiment's final massive 450-volt shock, though many were very uncomfortable doing so; at some point, every participant paused and questioned the experiment; some said they would refund the money they were paid for participating in the experiment. Throughout the experiment, subjects displayed varying degrees of tension and stress. Subjects were sweating, trembling, stuttering, biting their lips, groaning, digging their fingernails into their skin, and some were even having nervous laughing fits or seizures.[1]

Milgram summarized the experiment in his 1974 article, "The Perils of Obedience", writing:

" The legal and philosophic aspects of obedience are of enormous importance, but they say very little about how most people behave in concrete situations. I set up a simple experiment at Yale University to test how much pain an ordinary citizen would inflict on another person simply because he was ordered to by an experimental scientist. Stark authority was pitted against the subjects' [participants'] strongest moral imperatives against hurting others, and, with the subjects' [participants'] ears ringing with the screams of the victims, authority won more often than not. The extreme willingness of adults to go to almost any lengths on the command of an authority constitutes the chief finding of the study and the fact most urgently demanding explanation.

Ordinary people, simply doing their jobs, and without any particular hostility on their part, can become agents in a terrible destructive process. Moreover, even when the destructive effects of their work become patently clear, and they are asked to carry out actions incompatible with fundamental standards of morality, relatively few people have the resources needed to resist authority.[8]

"

The original Simulated Shock Generator and Event Recorder, or shock box, is located in the Archives of the History of American Psychology.

Later, Milgram and other psychologists performed variations of the experiment throughout the world, with similar results.[9] Milgram later investigated the effect of the experiment's locale on obedience levels by holding an experiment in an unregistered, backstreet office in a bustling city, as opposed to at Yale, a respectable university. The level of obedience, "although somewhat reduced, was not significantly lower." What made more of a difference was the proximity of the "learner" and the experimenter. There were also variations tested involving groups.

Thomas Blass of the University of Maryland, Baltimore County performed a meta-analysis on the results of repeated performances of the experiment. He found that the percentage of participants who are prepared to inflict fatal voltages remains remarkably constant, 61–66 percent, regardless of time or country.[10][11]

None of the participants who refused to administer the final shocks insisted that the experiment itself be terminated, nor left the room to check the health of the victim without requesting permission to leave, as per Milgram's notes and recollections, when fellow psychologist Philip Zimbardo asked him about that point.[12]

Milgram created a documentary film titled Obedience showing the experiment and its results. He also produced a series of five social psychology films, some of which dealt with his experiments.

Before conducting the experiment, Milgram polled fourteen Yale University senior-year psychology majors to predict the behavior of 100 hypothetical teachers. All of the poll respondents believed that only a very small fraction of teachers (the range was from zero to 3 out of 100, with an average of 1.2) would be prepared to inflict the maximum voltage. Milgram also informally polled his colleagues and found that they, too, believed very few subjects would progress beyond a very strong shock.[1] Milgram also polled forty psychiatrists from a medical school, and they believed that by the tenth shock, when the victim demands to be free, most subjects would stop the experiment. They predicted that by the 300-volt shock, when the victim refuses to answer, only 3.73 percent of the subjects would still continue and, they believed that "only a little over one-tenth of one percent of the subjects would administer the highest shock on the board."[7]

In Milgram's first set of experiments, 65 percent (26 of 40)[1] of experiment participants administered the experiment's final massive 450-volt shock, though many were very uncomfortable doing so; at some point, every participant paused and questioned the experiment; some said they would refund the money they were paid for participating in the experiment. Throughout the experiment, subjects displayed varying degrees of tension and stress. Subjects were sweating, trembling, stuttering, biting their lips, groaning, digging their fingernails into their skin, and some were even having nervous laughing fits or seizures.[1]

Milgram summarized the experiment in his 1974 article, "The Perils of Obedience", writing:

| " | The legal and philosophic aspects of obedience are of enormous importance, but they say very little about how most people behave in concrete situations. I set up a simple experiment at Yale University to test how much pain an ordinary citizen would inflict on another person simply because he was ordered to by an experimental scientist. Stark authority was pitted against the subjects' [participants'] strongest moral imperatives against hurting others, and, with the subjects' [participants'] ears ringing with the screams of the victims, authority won more often than not. The extreme willingness of adults to go to almost any lengths on the command of an authority constitutes the chief finding of the study and the fact most urgently demanding explanation.

Ordinary people, simply doing their jobs, and without any particular hostility on their part, can become agents in a terrible destructive process. Moreover, even when the destructive effects of their work become patently clear, and they are asked to carry out actions incompatible with fundamental standards of morality, relatively few people have the resources needed to resist authority.[8]

| " |

The original Simulated Shock Generator and Event Recorder, or shock box, is located in the Archives of the History of American Psychology.

Later, Milgram and other psychologists performed variations of the experiment throughout the world, with similar results.[9] Milgram later investigated the effect of the experiment's locale on obedience levels by holding an experiment in an unregistered, backstreet office in a bustling city, as opposed to at Yale, a respectable university. The level of obedience, "although somewhat reduced, was not significantly lower." What made more of a difference was the proximity of the "learner" and the experimenter. There were also variations tested involving groups.

Thomas Blass of the University of Maryland, Baltimore County performed a meta-analysis on the results of repeated performances of the experiment. He found that the percentage of participants who are prepared to inflict fatal voltages remains remarkably constant, 61–66 percent, regardless of time or country.[10][11]

None of the participants who refused to administer the final shocks insisted that the experiment itself be terminated, nor left the room to check the health of the victim without requesting permission to leave, as per Milgram's notes and recollections, when fellow psychologist Philip Zimbardo asked him about that point.[12]

Milgram created a documentary film titled Obedience showing the experiment and its results. He also produced a series of five social psychology films, some of which dealt with his experiments.

Applicability to Holocaust

Milgram sparked direct critical response in the scientific community by claiming that "a common psychological process is centrally involved in both [his laboratory experiments and Nazi Germany] events." Professor James Waller, Chair of Holocaust and Genocide Studies at Keene State College, formerly Chair of Whitworth College Psychology Department, expressed the opinion that Milgram experiments do not correspond well to the Holocaust events:[18]

- The subjects of Milgram experiments, wrote James Waller (Becoming Evil), were assured in advance that no permanent physical damage would result from their actions.However, the Holocaust perpetrators were fully aware of their hands-on killing and maiming of the victims.

- The laboratory subjects themselves did not know their victims and were not motivated by racism. On the other hand, the Holocaust perpetrators displayed an intense devaluation of the victims through a lifetime of personal development.

- Those serving punishment at the lab were not sadists, nor hate-mongers, and often exhibited great anguish and conflict in the experiment, unlike the designers and executioners of the Final Solution (see Holocaust trials), who had a clear "goal" on their hands, set beforehand.

- The experiment lasted for an hour, with no time for the subjects to contemplate the implications of their behavior. Meanwhile, the Holocaust lasted for years with ample time for a moral assessment of all individuals and organizations involved.[18]

In the opinion of Thomas Blass—who is the author of a scholarly monograph on the experiment (The Man Who Shocked The World) published in 2004—the historical evidence pertaining to actions of the Holocaust perpetrators speaks louder than words:

" Milgram's approach does not provide a fully adequate explanation of the Holocaust. While it may well account for the dutiful destructiveness of the dispassionate bureaucrat who may have shipped Jews to Auschwitz with the same degree of routinization as potatoes to Bremerhaven, it falls short when one tries to apply it to the more zealous, inventive, and hate-driven atrocities that also characterized the Holocaust.

Milgram experiment - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Milgram experiment on obedience to authority figures was a series of social psychology experiments conducted by Yale University psychologist Stanl...

Preview by Yahoo

Milgram sparked direct critical response in the scientific community by claiming that "a common psychological process is centrally involved in both [his laboratory experiments and Nazi Germany] events." Professor James Waller, Chair of Holocaust and Genocide Studies at Keene State College, formerly Chair of Whitworth College Psychology Department, expressed the opinion that Milgram experiments do not correspond well to the Holocaust events:[18]

- The subjects of Milgram experiments, wrote James Waller (Becoming Evil), were assured in advance that no permanent physical damage would result from their actions.However, the Holocaust perpetrators were fully aware of their hands-on killing and maiming of the victims.

- The laboratory subjects themselves did not know their victims and were not motivated by racism. On the other hand, the Holocaust perpetrators displayed an intense devaluation of the victims through a lifetime of personal development.

- Those serving punishment at the lab were not sadists, nor hate-mongers, and often exhibited great anguish and conflict in the experiment, unlike the designers and executioners of the Final Solution (see Holocaust trials), who had a clear "goal" on their hands, set beforehand.

- The experiment lasted for an hour, with no time for the subjects to contemplate the implications of their behavior. Meanwhile, the Holocaust lasted for years with ample time for a moral assessment of all individuals and organizations involved.[18]

In the opinion of Thomas Blass—who is the author of a scholarly monograph on the experiment (The Man Who Shocked The World) published in 2004—the historical evidence pertaining to actions of the Holocaust perpetrators speaks louder than words:

| " | Milgram's approach does not provide a fully adequate explanation of the Holocaust. While it may well account for the dutiful destructiveness of the dispassionate bureaucrat who may have shipped Jews to Auschwitz with the same degree of routinization as potatoes to Bremerhaven, it falls short when one tries to apply it to the more zealous, inventive, and hate-driven atrocities that also characterized the Holocaust. |

Milgram experiment - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Milgram experiment on obedience to authority figures was a series of social psychology experiments conducted by Yale University psychologist Stanl...

| |||||||

Preview by Yahoo

| |||||||

No comments:

Post a Comment