March 18, 2014

Overthinking It

The Big Questions from the 2014 SABR Analytics Conference

When I got back from last year's SABR Analytics Conference in Phoenix, I had a bunch of questions bouncing around in my brain. So I wrote 15 of them down in a piece for BP, as much to sort through them myself as to relay what I'd heard from the many presenters, panelists, and team employees who attended the three-day event. A year later, most of those questions are still stuck in my head. But the more I think about baseball, the more questions I collect, so those 15 have since been joined by many other mysteries.

The third annual SABR Analytics Conference wrapped up in Arizona on Saturday, and I'm back with a fresh batch of questions inspired by what I saw. (Because some presentations were scheduled opposite each other, I couldn't attend them all, but I've at least seen the slides from the ones that I missed. You can listen to audio and/or view the PowerPoint from many of the panels and presentations at the SABR Analytics site.)

Are players healthier now than they used to be?

The less information available on a given subject, the easier it is to manipulate the data we do have into supporting a preconceived notion. If you like the idea of trying to preserve pitchers by limiting pitch counts and innings, you'll point to the many promising careers that were ended by arm injuries decades ago, when pitchers were worked harder. If you miss the days when outings were longer and bullpens were smaller, you'll point to every arm injury today (and there are plenty to point to) as proof that our efforts to protect pitchers have had the opposite effect.

The less information available on a given subject, the easier it is to manipulate the data we do have into supporting a preconceived notion. If you like the idea of trying to preserve pitchers by limiting pitch counts and innings, you'll point to the many promising careers that were ended by arm injuries decades ago, when pitchers were worked harder. If you miss the days when outings were longer and bullpens were smaller, you'll point to every arm injury today (and there are plenty to point to) as proof that our efforts to protect pitchers have had the opposite effect.

The truth is, we don't really know whether the evolution of pitcher usage has made pitchers more or less safe, because we don't have a baseline injury rate to compare to today's. Until 2010, MLB didn't have any sophisticated injury tracking system; teams kept track of injuries on sheets of paper they kept in filing cabinets, and the thoroughness of those records varied depending on the doctor and training staff. As Dodgers trainer Stan Conte said on SABR's "Medical Analysis and Injury Prevention" panel, pre-2010 teams couldn't even tell whether they'd reduced their rate of hamstring strains from what it had been a few years before, let alone whether pitchers were suffering fewer serious injuries than they had in the 1970s. It doesn't help that the terminology used to describe injuries has changed over time. As Conte discovered when he looked into the recent meteoric rise of oblique injuries in baseball, it's not that players of the past never strained their obliques, it's that the same injury used to be referred to as a "ribcage" problem.

BP's Corey Dawkins has gone to great efforts to collect historical DL data for pitchers, but what we have isn't comprehensive. Even if it were, it might be misleading, since injured pitchers of the past weren't always placed on the disabled list—sometimes they just went home. And while we could compare innings totals or career lengths, it's tough to account for the fact that the same number of innings might mean many more pitches today, or that those innings might be more stressful because of increased competition. (Conte disclosed that the Dodgers had done a study on "stressful innings," looking for a connection between injury rates and high-pitch-count innings. That study didn't turn up any correlation, but they're redoing it right now with leverage index substituted for pitch count.)

I'm not saying there's no way we can establish whether modern methods of protecting pitchers have helped, but building a narrative based on cherry-picked injuries from different eras doesn't get us any closer to a conclusion. I say Score, you say Santana, let's call the whole thing off.

What are the truths about Tommy John surgery?

The injury prevention panel spent a lot of time discussing Tommy John surgery—and this was before the bad news about Medlen, Parker, Corbin & Co. Conte noted that TJ rates have remained roughly constant at 18-20 per year (except for a spike in 2012). Historically, pitchers have lost more time to shoulder injuries than elbow injuries, but that relationship has reversed lately, probably because it's become more common for doctors to advise rest and rehab to treat shoulder problems rather than recommending a risky surgery.

The injury prevention panel spent a lot of time discussing Tommy John surgery—and this was before the bad news about Medlen, Parker, Corbin & Co. Conte noted that TJ rates have remained roughly constant at 18-20 per year (except for a spike in 2012). Historically, pitchers have lost more time to shoulder injuries than elbow injuries, but that relationship has reversed lately, probably because it's become more common for doctors to advise rest and rehab to treat shoulder problems rather than recommending a risky surgery.

In a large-scale, long-term survey of pitchers who underwent ligament replacement surgery, Conte said, 85 percent got back to their pre-injury performance level. Most returned to play in 12 months, though their statistics (and their velo) didn't completely recover for 18 months. Among major-league pitchers, though, only 74 percent returned, and it tended to take closer to 16 months.

Conte mentioned that roughly 40 percent of parents and coaches of amateur players think that it's okay for a young pitcher to undergo Tommy John surgery before presenting any symptoms, believing that it will make him throw harder. However, that's mostly a myth. Some guys do throw harder after the surgery, but only because A) they were pitching hurtbefore the surgery, B) they had to take time off from throwing, which gave their body time to recover, or C) they got into better shape and/or cleaned up their mechanics during the rehab process.) Even for pitchers who return to the same performance level after the surgery, the first graft doesn't last forever. Sometimes it fails within a year or two (as it did forDaniel Hudson) if the surgery is sloppy, but even if everything goes well, it often fails in 8-9 years. Because pitchers have had TJ at earlier ages in recent years, we're seeing more and more two-time TJ'ers, Medlen and Parker among them. The sample is still small enough that we can't be sure of the recovery rate, but early signs are encouraging, though it tends to take two-timers longer to return.

How could bullpens become more flexible?

Moderator Jon Sciambi brought up the tyranny of rigid bullpen roles on the "Analytics from the Players' View" panel withBrandon McCarthy and Brian Bannister. Whenever we internet types suggest that an effective reliever might be more valuable if used in crucial situations (whenever they happen to occur) rather than assigned to a specific inning, we're told that players prefer predefined roles. The implication is that pitchers perform better if they know when their outing is likely to come and can prepare accordingly.

Moderator Jon Sciambi brought up the tyranny of rigid bullpen roles on the "Analytics from the Players' View" panel withBrandon McCarthy and Brian Bannister. Whenever we internet types suggest that an effective reliever might be more valuable if used in crucial situations (whenever they happen to occur) rather than assigned to a specific inning, we're told that players prefer predefined roles. The implication is that pitchers perform better if they know when their outing is likely to come and can prepare accordingly.

Both pitchers on the panel agreed that bullpens would benefit from more fluid roles, but they warned that the way things work now is too deeply ingrained for an open-minded manager to make a change on his own. According to McCarthy, a team that wanted to take advantage of an inefficiency in reliever usage would have to adjust its philosophy at every level of the organization. As it is, relievers are assigned to specific roles even at the lower levels of the minors, before it's clear who has closer potential and whose ceiling is a setup role. If a team taught bullpen flexibility from the start, there would be no culture shock at the major-league level, except for players imported from more traditional organizations. And those players, at least, would know exactly what to expect.

So would it work? To hear McCarthy tell it, this is a clear case of "like it or lump it." Players might not be pleased, but they'd adapt and move on. The reason why it might fly, he said, is that it wouldn't present a clear threat to any current player's career. To use McCarthy's comparison, telling relievers that they might pitch at any time from the sixth to the ninth isn't like telling Billy Hamilton that he has to stop stealing. No pitcher would be out of a job because a team decided to label its relievers less clearly. Given time to get used to the idea (and to see how well it worked), most players would accept leverage-based bullpen usage as the new normal.

Has the standardized strike zone made plate discipline more valuable?

We know that balls and strikes have been called both more accurately and more consistently since QuesTec and PITCHf/x gave us something to measure umpires against. (As Sam Miller observed in his review of Kerry Wood's 20-strikeout game, the difference between today's strike zone and the zone of even 15 years ago is evident to the eye.) Players today can be confident that they won't see strikes called way off the outside edge of the plate, and they can also expect one home-plate umpire's strike zone to resemble the rest.

We know that balls and strikes have been called both more accurately and more consistently since QuesTec and PITCHf/x gave us something to measure umpires against. (As Sam Miller observed in his review of Kerry Wood's 20-strikeout game, the difference between today's strike zone and the zone of even 15 years ago is evident to the eye.) Players today can be confident that they won't see strikes called way off the outside edge of the plate, and they can also expect one home-plate umpire's strike zone to resemble the rest.

This is a good thing, from a fan perspective, but we rarely consider the possible implications for players, a subject that surfaced (briefly) during the injury prevention panel. For instance, does the standardization of the strike zone make plate discipline a more valuable skill? Now that the zone is less prone to fluctuations from one day to the next, maybe the ability to distinguish a ball from a strike is worth more to teams. (We could check to see whether they're paying more for it, perhaps.) And maybe we can assess plate discipline skill more quickly, now that it's less subject to umpire influence. Does plate discipline stabilize more quickly in 2014 than it did a decade ago? That, too, could be checked.

It's also possible that hitters who excel at picking up on each umpire's personal strike zone—and veterans who gain the same insight from experience—might be less valuable today, due to the decreased variation between umps.

Is team chemistry more important in baseball than in other sports?

The standard line is that chemistry is less important in baseball than it is in sports that require in-game coordination, on-the-fly play-running, and a good feel for one's fellow players. Baseball is structured as a series of discrete, one-on-one matchups (for the most part), so it's not vital for players to feel any fondness for each other or to communicate clearly on the game is going on. Players who find each other abhorrent off the field get along fine after first pitch: The batter doesn't need someone to set a pick to give him a clear look at the pitcher, the first baseman doesn't need to signal for an assist when the shortstop gloves a grounder, and so on.

The standard line is that chemistry is less important in baseball than it is in sports that require in-game coordination, on-the-fly play-running, and a good feel for one's fellow players. Baseball is structured as a series of discrete, one-on-one matchups (for the most part), so it's not vital for players to feel any fondness for each other or to communicate clearly on the game is going on. Players who find each other abhorrent off the field get along fine after first pitch: The batter doesn't need someone to set a pick to give him a clear look at the pitcher, the first baseman doesn't need to signal for an assist when the shortstop gloves a grounder, and so on.

Maybe we're thinking about this the wrong way. In his talk about team chemistry on Friday, SABR President Vince Gennaro made the case that chemistry is more important in baseball because of the length of the season and the grind of 162 games (plus spring training and, perhaps, the playoffs). In Vince's view, baseball players are more interdependent—if not during games, then during all the time between games. The players Vince interviewed told him that they see their teammates more than they see their families, so it makes sense that they'd benefit from a tighter-knit traveling support system.

Is team chemistry in baseball more important than it used to be?

On the podcast last March, Sam Miller and I discussed whether chemistry in baseball is less important than it used to be because players aren't confined to close quarters to the extent that they once were. Clubhouses are a lot larger than they once were (outside of Wrigley Field and Fenway Park, anyway), players take plane trips instead of train trips and have their own hotel rooms, etc. All of that translates to less time spent in confined spaces, and perhaps less importance placed on the ability to get along.

On the podcast last March, Sam Miller and I discussed whether chemistry in baseball is less important than it used to be because players aren't confined to close quarters to the extent that they once were. Clubhouses are a lot larger than they once were (outside of Wrigley Field and Fenway Park, anyway), players take plane trips instead of train trips and have their own hotel rooms, etc. All of that translates to less time spent in confined spaces, and perhaps less importance placed on the ability to get along.

As Gennaro argued, though, good chemistry can create highly motivated players who work longer hours and prepare more thoroughly for their opponents. That might be a bigger deal than it once was. At one time, the difference between a driven player and one who was just playing for the paycheck might have meant the difference between getting a good night's sleep and playing hung over. But as Gennaro put it, we're living in an "age of empowerment" in which motivated players have more ways to separate themselves from the pack. By adhering strictly to a diet/nutrition or strength/flexibility program, or by studying PITCHf/x and HITf/x info and advance scouting reports, players who internalize an obligation to their organization and their teammates can get more out of their natural talent than was possible for players of earlier eras.

As Bannister said, "[Studying stats] was my steroids." It's in clubs' best interest to encourage any performance-enhancing process that can't result in a suspension, so we might start to see more teams trying to instill a thirst for knowledge during the development process. On the last day of the conference, Kyle Evans, the Cubs' Director of Video and Advance Scouting, said that his organization—which recently dismissed its uniformed psychologist—is trying to produce players who always look for an edge and exploit all advantages in addition to their talent. That may not what we typically think of when we talk about chemistry, but it probably should be.

What's the future of automated tracking technology?

At the Sloan conference earlier this month, we got our first glimpse of MLBAM's new field-tracking technology. At SABR, we got a look at an alternative tracking tech from Sportvision, the company behind (the evidently abandoned) FIELDf/x. The presentation (which began with a reminder that yes, Sportvision is still a partner of MLBAM) showed off a system tentatively dubbed BIOf/x. This one isn't intended to track everything that takes place on the field. It focuses specifically on the pitcher's delivery and the batter's swing (though it might eventually expand to include other players).

At the Sloan conference earlier this month, we got our first glimpse of MLBAM's new field-tracking technology. At SABR, we got a look at an alternative tracking tech from Sportvision, the company behind (the evidently abandoned) FIELDf/x. The presentation (which began with a reminder that yes, Sportvision is still a partner of MLBAM) showed off a system tentatively dubbed BIOf/x. This one isn't intended to track everything that takes place on the field. It focuses specifically on the pitcher's delivery and the batter's swing (though it might eventually expand to include other players).

BIOf/x captures the position of the bat or selected body parts at a moment in time: for pitchers, the location of the plant foot, shoulder at release, elbow at release, and hand at release, and for batters, the hands at the point of contact (or the point at which the bat and ball are on the same plane, in the case of a swing-and-miss), the tip of the bat at point of contact (or the point at which the bat and ball are on the same plane, in the case of a swing-and-miss), and the location of the back and front foot.

Goldbeck wouldn't say how exactly the data was captured (though presumably it's through some application of Sportvision's camera technology), or when the system would be finished. It's still in the prototyping stage, with data only from the O.Co Coliseum last September and October AFL action in Mesa, and it can't yet capture multiple points along the same plane, which would enable Sportvision to measure acceleration and mechanics from first movement to follow-through. The greatest limitation of Trackman and PITCHf/x is that they don't tell us how a pitcher got to the point at which he released the ball. And the greatest limitation of the current methods of measuring mechanics is that they require the pitcher to wear cumbersome equipment and can't be used in game, which means that they might not be capturing a completely natural motion. If it works, BIOf/x would address both issues.

The possibilities are enticing: the ability to measure stride length and extension, arm slot and arm and shoulder angles, the consistency of a pitcher's landing spot, the length of his release time, a batter's bat path and speed, and so on. One of the cooler applications is the ability to determine where the bat struck the ball—or if it didn't, why it missed. Think about that: Right now, we know how often a hitter whiffs when he swings. But we don't know whether he has timing issues or problems with seeing the ball. Does he tend to be early or late, or does he tend to swing under or over the ball (or both)? One of those causes might be more coachable/correctable than the other.

BIOf/x has its limitations, but it could complement MLBAM's system, which can't currently track a player's extremities. Until one system can see it all, the two could work in concert to cover everything important that takes place on the field.

What's the future of manual data collection?

On Friday, Baseball Info Solutions' Ben Jedlovec gave a talk about "The Anatomy of the Stolen Base," based on data BIS has begun to collect over the past few years: runner times to second, catcher pop times, and pitcher delivery times. (The company will track catcher throwing accuracy starting this season) With that information, BIS has developed a model that spits out an expected success rate for any runner-pitcher-catcher combination. Jedlovec didn't present any data for left-handed pitchers, and the model, which uses average times for each player on stolen base attempts as inputs, may overestimate the expected success rate of a really fast runner, since the pitcher and catcher typically speed up their releases with a known threat to steal on base. Despite that limitation, the data looked like it would be useful to teams that haven't hired interns to capture the same information internally.

On Friday, Baseball Info Solutions' Ben Jedlovec gave a talk about "The Anatomy of the Stolen Base," based on data BIS has begun to collect over the past few years: runner times to second, catcher pop times, and pitcher delivery times. (The company will track catcher throwing accuracy starting this season) With that information, BIS has developed a model that spits out an expected success rate for any runner-pitcher-catcher combination. Jedlovec didn't present any data for left-handed pitchers, and the model, which uses average times for each player on stolen base attempts as inputs, may overestimate the expected success rate of a really fast runner, since the pitcher and catcher typically speed up their releases with a known threat to steal on base. Despite that limitation, the data looked like it would be useful to teams that haven't hired interns to capture the same information internally.

But for how long? It was hard to watch that talk a few hours after getting another glimpse of a maturing motion-tracking technology and not wonder whether the painstaking process of pulling information from video is on the way out. There's still a several-company cottage industry that sells manually collected data to teams, but which would you rather have: a video scout with a stopwatch embedded in his proprietary video-viewing software, or an automated camera- and/or radar-based system that promises near-perfect precision? Probably both, until it's clear that the latter will work (which could take a while). But if MLBAM's and Sportvision's technology comes to fruition, it will be interesting to see whether the human alternatives find a new niche—analyzing the automated info?—or go the way of the Playograph.

Are front-office executives about to be rich?

A couple weeks ago, Lewie Pollis published an excerpt from his thesis at BP in which he laid out a case that the market for MLB front-office employees is not rational. As Lewie explained, the current front-office salary structure pays employees (from general managers on down) as if there's little to no difference in true talent between them. What that excerpt lacked was any evidence about what the actual difference between them might be.

A couple weeks ago, Lewie Pollis published an excerpt from his thesis at BP in which he laid out a case that the market for MLB front-office employees is not rational. As Lewie explained, the current front-office salary structure pays employees (from general managers on down) as if there's little to no difference in true talent between them. What that excerpt lacked was any evidence about what the actual difference between them might be.

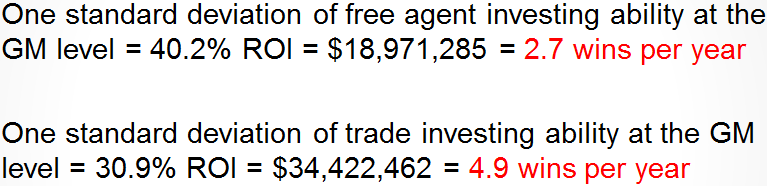

Pollis supplied some of that evidence at SABR by comparing team performance in completed trades and free-agent signings since 1996. By regressing that performance and attributing it to the general managers who made the moves, Pollis came up with an estimate of the standard deviation in GM ability (when it comes to trades and signings, specifically):

Combine those two figures, and one standard deviation comes to 7.6 wins—over $53 million, by Pollis' calculation of what teams paid for free-agent wins last winter. By contrast, Theo Epstein (the highest-paid GM, according to Pollis' presentation) makes $3.7 million per year.

Although that estimate gives the GM credit for any input from his subordinates, Pollis also included a breakdown of what those underlings might be worth if the SD in GM ability is accurate:

In other words, even an intern who's worth 0.1 wins more than a replacement-level alternative might be worth seven figures.

The size of some of these numbers might strain credulity, but Pollis' thesis—that teams would get more bang for their buck in the front office than they would in free agency—seems sound. The room in which Pollis presented was full of front-office employees who would be happy to be better paid. What we don't know is whether any owners can be persuaded to see things the same way. If one could, the short-term advantage could be considerable.

Are front offices about to be bigger?

If Pollis is right, then not only should teams be paying more for front-office talent, they should be bringing in more of it, particularly while prices are low. At some point, of course, communication becomes an issue, but it doesn't appear that front offices have expanded to the point that adding additional brainpower would lead to too many cooks in the kitchen, provided that the new hires were managed efficiently.

If Pollis is right, then not only should teams be paying more for front-office talent, they should be bringing in more of it, particularly while prices are low. At some point, of course, communication becomes an issue, but it doesn't appear that front offices have expanded to the point that adding additional brainpower would lead to too many cooks in the kitchen, provided that the new hires were managed efficiently.

So what kind of front-office employee is about to be in vogue? According to Chris Marinak, MLB's Senior VP of League Economics & Strategy, it could be the "medical analyst." On the injury prevention panel, Marinak mentioned that some baseball ops departments—particularly ones on clubs without a research-oriented trainer like Conte—now contain medical analysts who report to the GM. Before and just after Moneyball, the hot new thing was to have a statistical analyst. Now that even the Phillies have started a stat department, teams have moved on to the next innovation. Investing in injury prevention seems like the perfect place to do it, since a medical analyst who could save a star a single DL stint would be worth a Pollis-approved amount of money. Conte noted that medical information tends to be "dirty data," but the league's new injury database makes better analysis possible. It's no coincidence that this is happening now.

Will we ever eliminate (or significantly reduce) injuries?

The injury prevention panel discussed the improved quality of medical data and the rise of medical analysts. Graham Goldbeck showed off Sportvision's new plan to monitor biomechanics in game. Jeff Zimmerman built on Josh Kalk'sresearch to develop a method for detecting pitcher injuries via PITCHf/x via in-game and full-season changes in velocity and decreases in zone rate and release point consistency. (Zimmerman's process produces some false positives and false negatives, and it can't prevent an injury from occurring, but it could potentially prevent one from being aggravated or reveal one that a pitcher is trying to hide.) Conte mentioned that many teams keep their training facilities open year-round in hopes of preventing players from working out without supervision, or talk to their trainers to make sure they're following an approved plan. Put it all together, and one could be forgiven for thinking that a significant reduction in the rate of serious injuries is inevitable.

The injury prevention panel discussed the improved quality of medical data and the rise of medical analysts. Graham Goldbeck showed off Sportvision's new plan to monitor biomechanics in game. Jeff Zimmerman built on Josh Kalk'sresearch to develop a method for detecting pitcher injuries via PITCHf/x via in-game and full-season changes in velocity and decreases in zone rate and release point consistency. (Zimmerman's process produces some false positives and false negatives, and it can't prevent an injury from occurring, but it could potentially prevent one from being aggravated or reveal one that a pitcher is trying to hide.) Conte mentioned that many teams keep their training facilities open year-round in hopes of preventing players from working out without supervision, or talk to their trainers to make sure they're following an approved plan. Put it all together, and one could be forgiven for thinking that a significant reduction in the rate of serious injuries is inevitable.

Well, not necessarily. Another injury panel participant, Dr. Glen Fleisig of the American Sports Medicine Institute, pointed out that ligaments and tendons will always be the weak links in the pitcher's delivery. We can make muscles stronger, and we can make mechanics cleaner, but we can't make those weak links much more robust. It may be, then, that no matter what we do—short of enhancing our bodies with mechanical parts—we'll never make a major dent in the kind of injuries that shorten pitchers' careers. That tension between the frailties of the flesh and the sophistication of the science and technology that we're increasingly bringing to bear will be at the heart of the battle to make the repetitive pitching motion something players can survive.

Is pitcher consistency a skill?

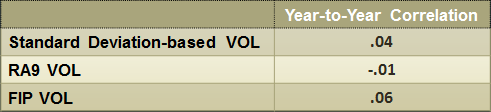

At some point in your time as a person who pays attention to baseball, you've probably been convinced that a certain pitcher is especially volatile, capable of having an excellent outing or falling to pieces depending on the day. Bill Petti developed and presented a metric (called VOL) to test this. The least consistent starter from 2009-13, according to VOL:Brandon Morrow, with Johan Santana and Francisco Liriano second and third. The most consistent: Kevin Correia, followed by Ryan Dempster and John Lannan. That sounds about right (though A.J. Burnett, who has a reputation for being inconsistent, shows up as the sixth-least-volatile starter).

At some point in your time as a person who pays attention to baseball, you've probably been convinced that a certain pitcher is especially volatile, capable of having an excellent outing or falling to pieces depending on the day. Bill Petti developed and presented a metric (called VOL) to test this. The least consistent starter from 2009-13, according to VOL:Brandon Morrow, with Johan Santana and Francisco Liriano second and third. The most consistent: Kevin Correia, followed by Ryan Dempster and John Lannan. That sounds about right (though A.J. Burnett, who has a reputation for being inconsistent, shows up as the sixth-least-volatile starter).

So VOL seems to do a good job of pinpointing the pitchers who have been volatile over a particular period of time. The question is whether those pitchers are any more likely than others to continue to be volatile in the future. Is there anything about certain pitchers that makes them inherently inconsistent?

Petti tried, but he couldn't find any year-to-year consistency in his measures of volatility:

As Petti noted, this could be because the metric takes more time to stabilize, or it could be because of something he hasn't accounted for. It could also be that individual pitchers are actually more or less volatile, but that those tendencies wash out for the pitcher population as a whole. For now, though, we have no evidence that some pitchers' performances fluctuate more than others relative to their average outing.

How much does scouting information improve player projections?

Quite a bit, apparently. Dave Allen and Kevin Tenenbaum compared three projections for minor-league players: one based on a "naïve" statistical model, one based on the more complex ZiPS projection system, and one informed by Kevin Goldstein's five-star prospect tiers at Baseball Prospectus from 2007-2012. The scouting-centric model won head-to-head showdowns with both of the others.

Quite a bit, apparently. Dave Allen and Kevin Tenenbaum compared three projections for minor-league players: one based on a "naïve" statistical model, one based on the more complex ZiPS projection system, and one informed by Kevin Goldstein's five-star prospect tiers at Baseball Prospectus from 2007-2012. The scouting-centric model won head-to-head showdowns with both of the others.

That shouldn't come as a shock: Scouts, after all, have access to stats, but the stats don't draw on the scouting grades. Not surprisingly, the method that makes use of more information wins. Still, it's nice to see that outcome confirmed. Teams, of course, have much more granular scouting grades than KG's old star system at their disposal, so they can probably build much more accurate projections.

What's the next hotbed of baseball talent?

A three-person panel on "The International Baseball Landscape" yielded three possible answers: China, Colombia, and Brazil. Pirates Director of Player Personnel Tyrone Brooks said he expected to see pro players from China in the next 2-3 years. (The Yankees signed two Chinese teenagers in 2007, but neither made it to the minors.) He reasoned that there are too many Chinese people (and thus too much Chinese talent) for some of them not to end up in American baseball, especially now that MLB has opened an academy in the country.

A three-person panel on "The International Baseball Landscape" yielded three possible answers: China, Colombia, and Brazil. Pirates Director of Player Personnel Tyrone Brooks said he expected to see pro players from China in the next 2-3 years. (The Yankees signed two Chinese teenagers in 2007, but neither made it to the minors.) He reasoned that there are too many Chinese people (and thus too much Chinese talent) for some of them not to end up in American baseball, especially now that MLB has opened an academy in the country.

Leonte Landino of ESPN Deportes said that he expects Colombia—which has produced young players such as Julio Teheran and Jose Quintana—to continue to be one of the fastest-growing sources of baseball talent over the next decade, thanks in part to Edgar Renteria's role in funding a fully operational league that sent a team to the most recent WBC qualifiers. Colombia's proximity to Venezuela makes it fairly easy for teams to scout, and Colombian players will often travel to Venezuela for tryouts.

Brazil was the third country mentioned. Brooks mentioned that the Pirates had just sent a scout to a showcase in Brazil for the first time and noted that the Andre Rienzo became the first major leaguer developed in Brazil when he debuted with the White Sox last year. (Yan Gomes was born in Brazil but drafted and developed in the US.) The center of Brazil's baseball development is Sao Paolo, which also houses the largest Japanese community outside of Japan (/Wikipedia), so Brazilian baseballers tend to adhere to a Japanese style of play.

How granular is baseball data going to get?

During his BIOf/x unveiling, Goldbeck said that we're "just going to keep drilling down further until there's nothing left." The question, then, is how much further we have to go until we get to that point. As Christina Kahrl asked a number of attendees, is sabermetrics still revolutionary, or have we reached a more evolutionary stage in which incremental progress is all we can expect?

During his BIOf/x unveiling, Goldbeck said that we're "just going to keep drilling down further until there's nothing left." The question, then, is how much further we have to go until we get to that point. As Christina Kahrl asked a number of attendees, is sabermetrics still revolutionary, or have we reached a more evolutionary stage in which incremental progress is all we can expect?

My guess? We have a long way to go before we run out of discoveries to make and drilling down to do.

Stray observations

- When asked about the level of familiarity with advance stats among major-league players, McCarthy estimated that 5-10 percent of big leaguers would know what FIP is.

- ESPN analyst and former Nationals and Indians manager Manny Acta (who cited BP's Mind Game as his favorite book) explained that his sabermetric conversion came in 2005 when a Mets clubhouse attendant told him about research that suggested that teams often had a better chance to score more runs before a sacrifice bunt. Acta, who was then the team's third-base coach, took the tip and sought out insights from stats. But the fact that the tip came from a clubhouse attendant says a lot about how slow some teams were to adapt, and how slow some of them still are to encourage communication and information sharing between the front office and field staff.

- One tidbit from the international baseball panel: The Dominican baseball academy that the Mariners just opened cost $4.2 million to build and will take $2-3 million to operate annually. No wonder teams with Dominican academies send players from Mexico and Venezuela to the DR rather than operate academies in each country.

- According to Goldbeck, Sportvision just began gathering PITCHf/x data from the first system installed at an NPB park.

- A couple other nuggets from Goldbeck's talk: Pitcher stride length (in Sportvision's sample) varied from 5-7 feet, with a mean of six feet. Mean extension was five feet, eight inches—most pitchers release the ball a few inches behind where they plant their front foot. The relationship between stride length and extension was weaker than expected, which could be because arm length varies independent of stride length, or because extension is affected by the degree at which the trunk tilts forward. The mean arm slot was 30 degrees, where 0 is sidearm and 90 is overhead. That's roughly a ¾ slot.

- And some nuggets from Jedlovec and BIS: The average right-handed pitcher's delivery time on a stolen base attempt since 2012 is 1.43 seconds. The average run time to second on a steal with a righty on the mound is 3.52 seconds. (Billy Hamilton had the fastest average time last season, at 3.31.) The average catcher's pop time since 2011 is 1.95 seconds, and 27 percent of stolen base attempts don't lead to catchable throws (either the catcher doesn't attempt to catch the runner, or he throws the ball into center). To produce a 50 percent caught stealing rate, the ball has to get to the glove of the player covering second 0.20-0.25 seconds before the runner arrives—if it gets there at the same time, the runner is safe 88 percent of the time. The most important takeaway: The pitcher has a greater impact on stolen base success rates than the catcher.

- I took two important lessons from Ken Rosenthal's one-on-one interview with Brewers owner Mark Attanasio. First: In baseball, budgets are made to be broken. Second: Sometimes a big signing is as simple as running into the right agent at Ryan Braun's wedding.

- Evans mentioned that player tracking is more advanced in some other sports, and that some soccer teams are tracking their players' heart rates during games via wearable sensors. He also said that that tech would be of less use in baseball, since baseball teams aren't looking for endurance athletes. Baseball players are conditioned differently (or in some cases, not conditioned at all).

- Bloomberg Sports VP Dan Cohen, who recently returned from a trip to Japan, noted that the Yokohama BayStars take their players on a two-day spiritual retreat during spring training. The A's adopted dual batting cages from Japan this year; don't be surprised to see spiritual retreats in 2015.

- After speaking to various team employees who attended the conference, it's hard to believe that one club recentlyspent $500,000 on a supercomputer. Many teams have surprisingly small (if not nonexistent) analytics budgets.

- During the SABR Defensive Index discussion, Baseball-Reference.com founder Sean Forman admitted to some frustration about the fact that teams are "incredibly opaque" about their involvement with analytics. On the prospects panel, the tone couldn't have been more different: MLB.com's Jonathan Mayo and Jim Callis said that teams are much more open about minor leaguers now that video is easier for the public to obtain (and now that prospects will tweet at you to tell you what pitch types they throw).

- On the panel on front-office decision-making, Mariners GM Jack Zduriencik and Bill Geivett and Bobby Evans of the Rockies and Giants, respectively, agreed that moves can come together much more quickly now that communication and access to information is almost instantaneous. Geivett mentioned being able to do a deal that was proposed two minutes before the trade deadline because both teams involved were so well informed about the players involved.

- Conte noted that elbow and shoulder injuries account for 53-57% of all time lost to injury at the major-league level. Hamstring strains are the most common injury, but they take a lot less time to recover.

- ESPN's Buster Olney, who moderated the injury prevention panel, wondered whether it might be possible for all free agents to undergo a physical at the start of the offseason to avoid failures and leaks later on. Marinak said that he thought three quarters of players might go for it, but that others (among them those who were still recovering or rehabbing from an injury) would strongly object. Conte said that even if players approved the plan, he'd still advise his team to perform another physical immediately before signing someone, in case an injury had occurred since the first physical.

There were, by my count, 25 talks, panels, or presentations at last week's SABR Analytics Conference in Phoenix. I couldn't attend all of them, since some overlapped, but I made it to as many as possible. I've already written about the most interesting thing I heard, but the Indians' sabermetric approach to marketing was just one of many intriguing topics that made me start scribbling notes during the three days I spent listening to smart people talk about baseball. (Many of those topics were brought up by Bill James, which probably isn't surprising.)

Below I've listed some of the questions asked (either explicitly or indirectly) at SABR that are still on my mind a week after the conference began. I don't have the answers to all of them, but that's okay, because, as James said, "The key is to find the questions." (Note: Only a few of the events are available online, there was no convenient place to put a computer, and I scribble only so fast, so I may have mixed up a detail or two.)

Should teams pamper their players?

Brian Kenny was the first featured speaker, and he spent much of his time talking about competitive advantages that he thinks teams still aren't exploiting. He cited an example from Soccernomics of one team that had an entire department devoted to treating its high-priced transfers like royalty, essentially offering them full concierge service from the moment they signed. According to Kenny,

Brian Kenny was the first featured speaker, and he spent much of his time talking about competitive advantages that he thinks teams still aren't exploiting. He cited an example from Soccernomics of one team that had an entire department devoted to treating its high-priced transfers like royalty, essentially offering them full concierge service from the moment they signed. According to Kenny,

They found that most of these players that would come in and transfer for big money, they'd be busts. And they'd be busts because they were uncomfortable, their family was uncomfortable, the change was more difficult than they thought. They were ignoring the psychological impact on that player. And one team in particular said, 'We are going to make sure all of our guys are as happy as they possibly can be,' and the results were tremendous. I think that's the next wave.

It's not as if most major leaguers have it hard, but it's reasonable to suggest that a team could distinguish itself by offering players more and more off-the-field perks, simultaneously optimizing its current players' performance and making itself more attractive to potential acquisitions.

Bill James wasn't buying it. Speaking the next day, James admitted that he'd had the same thought himself, and that what Kenny had proposed was literally true: "If you do more to make sure your employees are comfortable, you'll get better results." But according to James, any advantage derived would be short-lived. James believes that happiness adheres to the "Law of Competitive Balance" he formulated in the 1983 Abstract, which states that certain forces tend to conspire against strong teams and in favor of weak teams in ways that reduce the difference between the two. He cited the findings from this study, which were summarized in a Forbes piece last November:

The study found that the overall happiness levels of lottery winners spiked when they won, but returned to pre-winning levels after just a few months. In terms of overall happiness, the lottery winners were not significantly happier than the non-winners. The accident victims were slightly less happy, but not by much. The study showed that most people have a set level of happiness and that even after life-changing events, people tend to return to that set point.

James concluded, "The same happens in a baseball team. If you try to make players happy all the time, what you wind up with is spoiled players who can't do anything for themselves, and they're not any happier than they would be. You just move the standards."

In other words, pampering a player might make him feel more at ease in the short term, but it wouldn't make him happier down the road. And it would mean more time and expense for the team.

Will the knuckleball ever be banned?

Brian Kenny believes that one day the knuckleball could be outlawed, like the spitball. Knuckleballers, Kenny says, are potentially too effective: they can throw more innings, work on shorter rest, and remain productive at more advanced ages than most pitchers. Up until now, teams have been willing to wait for the occasional knuckleballer to come along, but Kenny sees an opportunity for some team to "open up an academy and start churning out these guys." If that were to happen, he suggests, knuckleballers could proliferate to a dangerous degree, endangering the tenuous pitcher-batter balance and forcing MLB to take action.

Brian Kenny believes that one day the knuckleball could be outlawed, like the spitball. Knuckleballers, Kenny says, are potentially too effective: they can throw more innings, work on shorter rest, and remain productive at more advanced ages than most pitchers. Up until now, teams have been willing to wait for the occasional knuckleballer to come along, but Kenny sees an opportunity for some team to "open up an academy and start churning out these guys." If that were to happen, he suggests, knuckleballers could proliferate to a dangerous degree, endangering the tenuous pitcher-batter balance and forcing MLB to take action.

Of course, if the knuckleball has the potential to be effective enough to upset baseball's competitive balance, why hasn't some team made more of an effort to develop knuckleball pitchers already? Kenny believes it's just a case of bias without basis. "There's a conditioning, a bias against valuing these guys, for no reason except it's, what, unmanly? It's a gimmick pitch?" he asked at SABR. "It's nonsense. What does it actually do? It gets guys out."

If you'd asked me why the knuckleball hasn't become more common, I probably would've said "because it's a hard pitch to throw." Perhaps there's something to that. But Bill James revealed another, equally persuasive reason I'd never considered. And he was speaking from experience:

"Theo [Epstein], when he was in Boston, was always trying to develop knuckleballers. He always had some plan about how he was going to develop knuckleballers, and it never worked. And it never worked because there's a long, long series of small barriers to it that are invisible from the outside."

Those barriers to knuckleballer development are simple, but significant: there's no one to coach them and no one to catch them. Since there are so few former knuckleballers, there are few coaches with specialized knowledge of the pitch who can nurture the next generation of knucklers. And since there are so few people who throw the pitch, there are just as few who can catch it. As a result, it's hard for a knuckleballer to throw a side session unless he wants to retrieve the ball himself. And he can't be brought in with runners on base, because those runners will score on passed balls. As James concluded, "It's just very, very hard to develop knuckleballers for reasons that are not really apparent until you try it." You can see some of that subtext in Jonathan Zeller's recent BP profile of Red Sox minor-league knuckleballer Steven Wright.

A knuckleball academy might solve some of those problems by being equipped with capable coaching and catching staffs, but eventually the knuckleballers would still have to face professional hitters, who probably wouldn't be willing to enroll in the academy and take BP against knuckleball cadets when they could be advancing their own careers. And when the time to face real hitters in actual games arrived, the same catching problems could crop up. There's also the possibility that hitters could become accustomed to the knuckleball if they saw it more often, which would make the pitch less effective.

Are high draft picks less likely to sign early extensions?

This is one question that research could settle. It was cited during the player development panel as a potential downside to drafting early. Players sign team-friendly extensions before they become free agents to ensure their families' financial security in the event of an injury. Therefore, the thinking goes, players who were picked early and got big bonuses might have less incentive to sign than late-rounders who outperformed their draft position but have very little tucked away in the bank.

This is one question that research could settle. It was cited during the player development panel as a potential downside to drafting early. Players sign team-friendly extensions before they become free agents to ensure their families' financial security in the event of an injury. Therefore, the thinking goes, players who were picked early and got big bonuses might have less incentive to sign than late-rounders who outperformed their draft position but have very little tucked away in the bank.

Of course, Evan Longoria, the patron saint of players who sign team-friendly extensions, was a third overall pick who got a $3 million bonus from Tampa Bay. To put that into perspective, Bloomberg Businessweek reported late last year that the average American with a bachelor's degree makes $2.4 million in his lifetime. So before Longoria had played a professional inning, he'd already earned more than the average college-educated American ever will. That's financial security for you. And he never even got his degree!

Could the minor leagues be better structured?

James suggested that the structure of the minor leagues doesn't lend itself to efficient player development, observing that a "system that develops when each individual follows his own selfish needs is often an inefficient system." He believes that "from the standpoint of the game as a whole, there would be huge advantages to restructuring the minor leagues so that players were not sorted as belonging to teams until they reached a much higher level." In such a system, the draft would be held when players were a year or two away from the majors; before that, they wouldn't be attached to any particular team. One possible side effect of that system: it might also reduce the importance of scouting, since teams would have more reliable performance data with which to compare players before making their picks.

James suggested that the structure of the minor leagues doesn't lend itself to efficient player development, observing that a "system that develops when each individual follows his own selfish needs is often an inefficient system." He believes that "from the standpoint of the game as a whole, there would be huge advantages to restructuring the minor leagues so that players were not sorted as belonging to teams until they reached a much higher level." In such a system, the draft would be held when players were a year or two away from the majors; before that, they wouldn't be attached to any particular team. One possible side effect of that system: it might also reduce the importance of scouting, since teams would have more reliable performance data with which to compare players before making their picks.

On what planet(s) did Ichiro Suzuki and Mariano Rivera originate?

At this point, SETI should probably just call off the search: Ichiro and Rivera are the most unusual life forms we're ever likely to encounter. Sportvision's Graham Goldbeck, who (presumably) gets paid to play with FIELDf/x, HITf/x, and COMMANDf/x all day, gave a presentation titled "Batted Ball Success by Depth in the Zone." Matt Eddy has a thorough write-up of the whole thing here, but I want to focus on what Goldbeck revealed about the two future Hall of Famers who regularly do things no one else does.

At this point, SETI should probably just call off the search: Ichiro and Rivera are the most unusual life forms we're ever likely to encounter. Sportvision's Graham Goldbeck, who (presumably) gets paid to play with FIELDf/x, HITf/x, and COMMANDf/x all day, gave a presentation titled "Batted Ball Success by Depth in the Zone." Matt Eddy has a thorough write-up of the whole thing here, but I want to focus on what Goldbeck revealed about the two future Hall of Famers who regularly do things no one else does.

HITf/x tracks the precise points in space at which batters make contact, and Goldbeck had data on over 600,000 balls in play since 2008 to examine (which, again, he probably got paid for). He found that batters who make contact with pitches well in front of the plate (intuitively) tend to pull the ball and hit for more power, while those who wait (or react more slowly) and hit the ball when it's closer to the catcher tend to go the other way and hit for less power. The average point of contact is about four inches in front of home plate, but max ISO on contact comes about eight inches earlier.

Goldbeck also found that contact points tend to stabilize quickly—according to Eddy, after about 25 balls in play. Except for Ichiro's. Ichiro's contact point was the least stable of any batter's: he hits pitches in front of the plate, deep in the zone, and everywhere in between. We already knew Ichiro had crazy bat control, but it's nice to see Sportvision's newfangled stats confirm it. I've been skeptical of claims that Ichiro could hit for much more power if he simply decided to try, but I'm a little less skeptical now.

And then there's Rivera. Goldbeck found that pitchers who induce contact deep in the zone tend to be hard throwers (which makes sense, since it's harder to catch up to their pitches). There were three notable exceptions to this general rule—relatively slow throwers who still induce deep contact. Two of them were Brad Ziegler and Randy Choate, specialist relievers with weird arm angles whom hitters can't get a good read on. The third was Mariano Rivera, who throws the same damn pitch every time.

When the two went head to head (which, sadly, we'll almost certainly never see again), Ichiro's weirdness won out: he hit .400/.438/.667 in 16 plate appearances against Rivera.

How big is baseball data going to get?

On Saturday, SABR president Vince Gennaro provided some figures about the exponential increase of baseball data over the last decade. He estimated that when Moneyball was published in 2003, the space required to store all statistical data on major-league games produced to that point–mostly box scores and some play-by-play logs—came to less than 1.5 gigabytes. The last five years have produced six percent of all big-league games ever played, but over 95 percent of the data about them (without counting minor-league data or fledgling FIELDf/x), since we're now storing so much information about players' processes as well as the outcomes of each play. All in all, we're up to roughly 30-40 gigabytes, with many more to come.

On Saturday, SABR president Vince Gennaro provided some figures about the exponential increase of baseball data over the last decade. He estimated that when Moneyball was published in 2003, the space required to store all statistical data on major-league games produced to that point–mostly box scores and some play-by-play logs—came to less than 1.5 gigabytes. The last five years have produced six percent of all big-league games ever played, but over 95 percent of the data about them (without counting minor-league data or fledgling FIELDf/x), since we're now storing so much information about players' processes as well as the outcomes of each play. All in all, we're up to roughly 30-40 gigabytes, with many more to come.

Gennaro stressed that we need both new methods and new hardware to process data on that scale. He mentioned that YarcData, a division of Cray ("the supercomputer company") that constructs and runs complex queries like the ones that produced the "pitcher clusters" he presented, uses computers with eight terabytes of RAM. The maximum amount of RAM the little laptop I'm using to type this can handle, assuming I'm willing to void the warranty, is eight gigabytes. It freezes for five minutes when I click on long email threads. Cray's computers can run a query in a couple of days that might take a year for most companies to complete, or calculate the Answer to the Ultimate Question of Life, the Universe, and Everything while Deep Thought is still stuck at the sign-in screen. That's the kind of processing power that some baseball teams might be about to have at their disposal.

One other tidbit from Gennaro's talk: when he analyzed pitcher clusters based on a whole host of process characteristics, he noticed that pitchers from the same organization were grouped together more often than he expected, which suggests that we might be underrating the extent to which coaching and organizational philosophies affect pitchers' approaches.

Do situational relievers make sense?

Recently, Bill James wrote, "Right or wrong, it is my opinion, until somebody can show me where I'm wrong, that carrying left-handers in the bullpen is a complete waste of time and resources." At SABR, he said he doubts that the compulsive pursuit of the pitching platoon advantage is worth more than 5-8 runs to most teams, much fewer than he thinks those teams could gain by expanding their benches, platooning position players, and using defensive replacements, pinch-hitters, and pinch-runners aggressively.

Recently, Bill James wrote, "Right or wrong, it is my opinion, until somebody can show me where I'm wrong, that carrying left-handers in the bullpen is a complete waste of time and resources." At SABR, he said he doubts that the compulsive pursuit of the pitching platoon advantage is worth more than 5-8 runs to most teams, much fewer than he thinks those teams could gain by expanding their benches, platooning position players, and using defensive replacements, pinch-hitters, and pinch-runners aggressively.

Someone asked James why the Red Sox still use what he believes to be a counterproductive strategy, and he explained that change isn't as simple as voicing an unsupported assertion and expecting John Farrell to adopt it immediately. A couple factors James might not be taking into account: first, the deterrent value of situational relievers. If a team knows its opponent has no southpaw in the pen, it can stack its lineup with lefties whenever a righty starts or a lefty starter leaves the game. And then there's the effect of forcing one's remaining bullpen guys to pitch in longer bursts, which would likely make them all a little less effective without the right mix of relievers. Some helplessness at the hands of a big lefty bat in the late innings wouldn't be the only downside to doing away with LOOGYs.

Are we smarter about baseball than we used to be?

The obvious answer is "yes," since we certainly know things now that we didn't before. But James isn't so sure. He believes that new fallacies inevitably arise to replace the old ones, and that "there will never be a shortage of ignorance—we're just doing different stupid things." To hear him tell it, the team he works for is as guilty of that as any. About the Red Sox' recent free agent signings, James said, "Some of them were terrible moves at the time we made them, and we should've known better."

The obvious answer is "yes," since we certainly know things now that we didn't before. But James isn't so sure. He believes that new fallacies inevitably arise to replace the old ones, and that "there will never be a shortage of ignorance—we're just doing different stupid things." To hear him tell it, the team he works for is as guilty of that as any. About the Red Sox' recent free agent signings, James said, "Some of them were terrible moves at the time we made them, and we should've known better."

Is the public "ahead," or are front offices?

Teams have armies of scouts and gigabytes of proprietary data at their disposal. But James believes that the public sector will always be ahead, because of its greater accumulated brainpower. According to James, team analytics departments are to public-sector statheads what the White House is to the press. The press is always complaining that the White House is slow to respond to various issues, but it's not because of incompetence; it's because the White House doesn't have the same information-gathering abilities as the combined power of the press corps.

Teams have armies of scouts and gigabytes of proprietary data at their disposal. But James believes that the public sector will always be ahead, because of its greater accumulated brainpower. According to James, team analytics departments are to public-sector statheads what the White House is to the press. The press is always complaining that the White House is slow to respond to various issues, but it's not because of incompetence; it's because the White House doesn't have the same information-gathering abilities as the combined power of the press corps.

I see his point. But still: all those scouts, and all those proprietary stats.

What weight should we assign to "scouts" and "stats"?

Okay, so we all agree that both scouting and statistical data are important, and we know that smart teams (read: all teams) synthesize the two. But does that mean we should assign the same weight to each one, or is there a better breakdown?

Okay, so we all agree that both scouting and statistical data are important, and we know that smart teams (read: all teams) synthesize the two. But does that mean we should assign the same weight to each one, or is there a better breakdown?

Dodgers President and part-owner Stan Kasten said he favors scouts 60-40, in a general sense. When it comes to in-game tactics, he's fully in favor of stats, since a run expectancy table can tell you what happened in thousands of identical situations that arose in the past. But he believes that while stats are great at telling us what has happened—in that respect, in fact, he acknowledges they can be close to perfect—they're not as useful in predicting the future. Kasten said that prospects aren't like base-out situations, since no two of them are exactly alike, so you can't make player development decisions like you make in-game moves.

One of Kasten's biggest laugh lines was something a respected rival GM told him: that he really likes analytics when they agree with what the scouts say. According to Kasten, that's the case 80 to 90 percent of the time.

What is clubhouse chemistry worth?

I mentioned this on Tuesday's podcast, but during the player panel, Brandon McCarthy, one of the game's most statistically savvy players, said that without Brandon Inge and Jonny Gomes—two players with a combined 2.8 WARPin Oakland—the 94-win 2012 A's might have been a 70-win team. Nick Piecoro later asked him to elaborate, and he did. I doubt McCarthy actually believes the effect was anywhere near that large; more likely he was just trying to counter the chemistry deniers with some hyperbole of his own.

I mentioned this on Tuesday's podcast, but during the player panel, Brandon McCarthy, one of the game's most statistically savvy players, said that without Brandon Inge and Jonny Gomes—two players with a combined 2.8 WARPin Oakland—the 94-win 2012 A's might have been a 70-win team. Nick Piecoro later asked him to elaborate, and he did. I doubt McCarthy actually believes the effect was anywhere near that large; more likely he was just trying to counter the chemistry deniers with some hyperbole of his own.

It's difficult to quantify team chemistry—we've tried—but it probably doesn't get us any closer to the answer when either "side" of the issue exaggerates its estimate of the impact for effect. It seems safe to say that it's not worth 20 wins—if teams believed that it were, Inge and Gomes would be making much more money—and it's not worth nothing. Can't we all agree that the true effect is somewhere between the extremes? If so, we can stop squabbling and start figuring out how to make our estimates more precise.

Are steroids still a problem?

James said "steroids are gone," though he later clarified that he thinks fewer than 1 percent of players are still using them. He wasn't including testosterone or HGH in that estimate, but he's impressed with the measures Major League Baseball has taken to eradicate the use of those substances. PEDs might still be a problem in a retrospective sense, and they'll continue to pop up as long as players from the "Steroid Era" are on the Hall of Fame ballot, but if James is to be believed, their impact on baseball today is negligible.

James said "steroids are gone," though he later clarified that he thinks fewer than 1 percent of players are still using them. He wasn't including testosterone or HGH in that estimate, but he's impressed with the measures Major League Baseball has taken to eradicate the use of those substances. PEDs might still be a problem in a retrospective sense, and they'll continue to pop up as long as players from the "Steroid Era" are on the Hall of Fame ballot, but if James is to be believed, their impact on baseball today is negligible.

How much does a pitcher's extension matter?

Unlike PITCHf/x, Trackman, a radar-based ball-tracking system, records a pitcher's actual release point. The closer that release point is to home plate, the less reaction time the hitter has, and the higher the perceived velocity of the pitch. According to Alan Nathan's SABR presentation, one foot of extension equates to about 1.5 miles per hour of perceived velocity. Fourteen big-league teams now have Trackman installed in their stadiums.

Unlike PITCHf/x, Trackman, a radar-based ball-tracking system, records a pitcher's actual release point. The closer that release point is to home plate, the less reaction time the hitter has, and the higher the perceived velocity of the pitch. According to Alan Nathan's SABR presentation, one foot of extension equates to about 1.5 miles per hour of perceived velocity. Fourteen big-league teams now have Trackman installed in their stadiums.

Naturally, taller pitchers tend to get more extension, but size isn't all that matters—so does stride length, among other things, which explains how David Robertson, who stands 5'11", can have better extension (and thus a "sneakier" fastball) than much more physically imposing pitchers. Teams are paying attention to pitcher extension, and so should we, to the extent that we can without access to the data.

Should front offices play a larger role in dictating in-game moves?

Brian Kenny thinks we're getting to the point at which teams will have a stat-savvy assistant GM in the clubhouse or the dugout, where he'll feed the manager information and offer advice on in-game moves. But Jed Hoyer says it's the front office's job to filter information for the manager, not to meddle with his moves: if players perceive that the front office is pulling the strings, it undermines the manager. On a separate panel, James echoed Hoyer's concern, saying, "You don't put a front office man in a suit in daily contact with the players." One potential solution: more analytically inclined bench coaches, something James thinks we're already seeing.

Brian Kenny thinks we're getting to the point at which teams will have a stat-savvy assistant GM in the clubhouse or the dugout, where he'll feed the manager information and offer advice on in-game moves. But Jed Hoyer says it's the front office's job to filter information for the manager, not to meddle with his moves: if players perceive that the front office is pulling the strings, it undermines the manager. On a separate panel, James echoed Hoyer's concern, saying, "You don't put a front office man in a suit in daily contact with the players." One potential solution: more analytically inclined bench coaches, something James thinks we're already seeing.

After the hiring of Walt Weiss and Mike Redmond, Colin Wyers wrote that teams might be moving toward inexperienced managers because it's easier for them to exert control over a skipper who isn't established. According to Hoyer, though, the trend toward younger managers might have an economic explanation: players make too much money now to be willing to ride buses in the bush leagues after they retire. If teams want former players to manage, they'll have to be willing to put up with some amount of on-the-job training.

What's the role of stats in the clubhouse?

According to McCarthy and Javier Lopez, stats can't be force-fed: if a player isn't prepared for them, they can cloud his approach. Pitchers who aren't overpowering may be more willing to embrace analytics because their margins for error are smaller and they're more open to exploiting any edge, but it's still easy to reach a point of information overload.

According to McCarthy and Javier Lopez, stats can't be force-fed: if a player isn't prepared for them, they can cloud his approach. Pitchers who aren't overpowering may be more willing to embrace analytics because their margins for error are smaller and they're more open to exploiting any edge, but it's still easy to reach a point of information overload.

Lopez said something interesting: he doesn't think that teams are really even trying to persuade players to alter their approaches with stats, or find players who'd be receptive to statistical persuasion. Instead, they're just targeting players who already do things that the stats say are good. Eventually, he believes that players will realize what approaches teams prefer in their players, and they'll try to do those things of their own accord, without any nudging from numbers guys.

On the GM panel, Rich Hahn emphasized how easy it is to lose a player's trust when citing statistics. Even if a statistical approach is sound 99 times out of 100, if it happens to backfire for a player the one time he tries it, he'll be much less inclined to listen the next time. So when you cite a stat, you have to be sure.

One other tidbit that I'll add here because it doesn't fit anywhere else in the article: McCarthy mentioned that he hates facing hitters who confuse him by doing things he doesn't expect. Among the most confusing hitters to face: Jeff Francoeur, because he swings when no one else would.

Ben Lindbergh is an author of Baseball Prospectus.

Click here to see Ben's other articles. You can contact Ben by clicking here

Click here to see Ben's other articles. You can contact Ben by clicking here

No comments:

Post a Comment