One of the things that has always fascinated me about baseball, and sports in general, is how players get better. What is it about the superstars that elevates them above the average players? What are the physical attributes, the mental and emotional requirements? In baseball, what are the visual skills that are necessary for success at the highest levels? When I was a player, the emphasis was on using this information to become a better player. When I became a coach, the emphasis changed to learning and developing the most effective methods to allow upcoming players to succeed.

Along the way, I saw examples in football, beginning with Gil Brandt of the Dallas Cowboys, using test protocols to more effectively identify talented college players for his team to draft. It was fascinating to see him use these physical tests, as well as mental and emotional tests, like the Wonderlich test, to identify the players with the highest chances of success, more efficiently than his competitors.

It seemed like a no-brainer intuitively, but in most sports, the coaches and administrators still use hunches and intuition and gut instinct to make these important personnel decisions. There was a great reluctance to use modern tools and knowledge from other fields to aid in the decisions. Baseball men feel that what was done 50-100 years ago to judge and draft players works just fine, thank you very much.

My gut instincts and intuition have always led me to believe that the things that have worked in other sports to improve scouting, talent identification and player development would also work in baseball.

The player draft in all sports that have one is a prime determinant of which teams will be successful in the future and which ones will fail, so the stakes are high. In spite of drafting lower than most of his competitors, a result f the Cowboys success, Brandt’s scouting department consistently identified and drafted better players in the later rounds of the drafts than some teams did in the first and second rounds. Clearly, he was doing things better and more efficiently than other teams in terms of scouting and talent identification.

As front office and scouting personnel left the Cowboys for other team’s years later, the rest of the NFL learned that Brandt was a proponent of using certain physical tests and measurements to compare players at similar positions. For lineman, he wanted large strong men, the larger and stronger the better. So rather than simply compare how well a player performed he would find out how many times the players he was interested in could bench press 225 lbs, for positions where speed was a large component of success or failure, he measured them in the 40 yard dash and so on. He felt that simply judging collegiate players by how they performed in a limited number of games, many times against inferior competition, was inefficient. Most of these test and procedures he developed have since shown to be effective at a statistically significant level. There is a strong correlation between the ranking of players in the battery of tests and future success in the NFL.

The crux of Brandt’s theory is if you give your coaches the players with the best athletic skill sets to succeed, then it’s the coaching staff’s job to teach them the specific sports skills to succeed at that level. That’s what coaches are paid to do.

Most sports teams are copycats, when one team is successful using a certain method or procedure, others begin to copy in droves in hope that the success would follow. The cost of failure in drafting unproductive and players in sorts is too high both economically, in terms of the amount of bonuses paid to high draft picks. Today, almost every team in the NFL participates in the NFL combine, however baseball has stuck with its tradition based scouting methods.

It’s my opinion and that of other coaches and trainers that I work with that the time has come for baseball to start using this type of approach to evaluate the players it chooses. Many top draft picks receive million dollar plus bonuses. With that financial windfall and the notoriety of being a high draft pick, comes a lot pressure. Many players who have the requisite physical skills wash out because they are not mentally tough enough to handle failure. Some don’t have a strong enough work ethic and succeeded at lower levels on the basis of their superior physical gifts. There are tests that other sports have used to identify these traits in athletes.

Once you have the battery of tests that correctly identify the physical, mental and emotional qualities you need in an athlete, you should be able to use that tool to more efficiently identify which players would make your team in a tryout setting or which players to draft in the professional setting. In both cases, the problem facing teams and coaches is there are simply too many players to evaluate in a limited amount of time. The inefficiency is that the scouting department is using poorly defined or subjective parameters to identify talent. In baseball, many scouts still used the old hand-me-down term “he has the good face” to describe a prospect they like and they believe has a high probability for future success. The problem being fifty different scouts are likely to give you fifty different opinions as to what the term means. It’s too subjective and vague. The tests bring a level of accuracy and precision that baseball has never had before.

Scouts and baseball men are very guarded about their traditions and procedures. It’s safer for them to fail “going by the book” than to fail doing something outside the box. That gets you fired. It will take an organization with guts to change the culture in their scouting and player development department to make the change. Or maybe we simply need a man with the courage and conviction of Gil Brandt. So far, I have used the same methodology at every level through high school baseball with excellent results. I would like to see it eventually make its way to the professional level. It would be simply revolutionary.

Training Differences of Baseball Players

This is a reprint of an article that appeared in Coach Peter's Baseball Tips Web Site. The site contains quite a few informative articles from baseball coaches from around the country. The site is a good resource for players and coaches alike, especially the Instructional Articles section.

http://www.baseballtips.com/playertraining.html

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Training Differences of Baseball Players vs. Other Athletes

Charles Slavik, President of Eagle Baseball Club

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

George Carlin did a classic bit of comedy on the differences between the sports of baseball vs. football, giving the impression that the two sports couldn’t be more opposite in terms of pace, terminology and other factors. We agree and would add that the training for each sport has to be different as well. Both sports are power oriented sports, but there are differences in how that power is expressed and trained.

Sport & Athlete Needs Assessment

The trainer has to assess the unique needs of the sport and allocate time to improving each quality within the athlete. Athletic abilities assessment should be made for each athlete to match the athlete’s needs to the sport based on the level of competition. Then the athlete has a clear roadmap of where they are and where they wish to go based on their motivation and goals.

All sports differ in terms of the relative importance various physical skills contribute to the game and to individual athlete’s performance. The movements in baseball are ballistic in nature and involve full-body activity. The ability to repeatedly perform near maximal level with limited rest bouts is necessary for baseball players.

Baseball players should not be trained to build excess bulk or muscle mass. They should focus on improving quick, reactive movements, increasing explosiveness and injury prevention, as well as improving speed and trunk rotation. This will lead to improved bat speed and ball velocity.

Energy Systems

Because of the anaerobic nature of the game, baseball players use the phosphagen system as the primary source of energy. About 80% of the body’s metabolic energy will come from the phosphagen system. Training programs involving sprinting and plyometric exercises under 10 seconds in duration that provide complete recovery are indicated. This type of training will improve speed and power development.

Rotational Movements

One of the key differences in baseball is that the main activities of hitting and throwing occur in a rotational plane of movement and are very ballistic or explosive in nature. Therefore, baseball players need to train rotationally with light weights and high speed. Exercise that emphasizes rotating the hips and torso using resistance from cables/pulleys, dumbbells and medicine balls are effective.

Players often lack abdominal or core strength. Abdominal crunches and various rotational twists with a medicine ball should be used to develop a strong muscular base in this area. This will focus on improving strength and power in the rotational muscles of the core area that are vital for swinging a bat or throwing a ball.

Shoulder Stability & Rotator Cuff Work

Another key difference is the unusually high stress placed on the shoulder joint generally and the rotator cuff muscles. The act of pitching occurs at an angular velocity at the shoulder joint approaching 7,000 degrees per second (almost 20 full circles) and is one of the fastest human movements. This places the shoulder joint and surrounding muscles at significant risk of injury from repetitive stress.

Exercises that strengthen the anterior and posterior shoulder muscles in a balanced manner are vital. The shoulder should be flexible to allow for adequate external rotation necessary to throw at high speeds. Deceleration is the phase of pitching most associated with injury. Specific exercises to develop the muscles responsible for deceleration (mainly the rotator cuff and scapula muscles) are crucial.

Plyometric exercises for the shoulder and upper body are useful due to the explosive nature of the pitching motion. Exercises for the rhomboids, lats, pectorals and shoulder area are necessary to throw at high speeds.

Bat Speed Training

Swinging the bat is a skill that is unique to baseball. Players need good lower body and core strength to develop power in the swing. These muscles need to be trained rotationally in a high-velocity, explosive manner.

Strong hip and leg muscles will initiate the swing, the core area then sequentially transfers the rotational speed to the torso and the arms to complete the swing. The efficient transfer of force from the lower body to the upper body, known as the kinetic chain principle, requires that there be muscular balance for optimal sequential transfer of forces.

Strong lats, triceps and forearms will help to continue bat acceleration through ball contact. Squats, bench presses, pull ups, forearm and triceps exercises will develop the potential for power. Bat Speed Training with heavy and light bats within a prescribed range will transfer that potential to the actual sports skill in a specific manner.

Ball Velocity Training

Throwing a baseball with high velocity is an explosive, full-body movement that requires total body development. Strong leg, hip and core muscles are crucial to transfer power from the ground, through the lower body to the torso and eventually to the arm and hand to provide a fast, whip-like release of the ball. The efficient transfer of force through the proper sequencing of body parts through the legs, hips, trunk, and upper limb to the ball is crucial.

In addition to strength training, a weighted ball program or medicine ball throwing progression can be utilized to improve velocity. This will improve the ability to generate power in the throwing muscles. The combination of a heavy load to build power and a light load to build arm speed, thrown in a prescribed manner, has been shown to improve throwing velocity safely.

The athlete should train for proper trunk rotation during arm cocking as well as strength and flexibility in order to generate angular velocity within the trunk for maximum ball velocity. Training should involve trunk rotational exercises to develop the obliques so that maximum arm speed can be generated.

Biomechanical Analysis

We use video analysis of the pitching and hitting mechanics of each player for technique analysis, fault correction and feedback, as well as for assessing progress at a later stage of the program

Visual Skills Training

We also incorporate visual skills training for batters since the ability to accurately track the baseball and predict where it’s going to be is crucial to a hitter. Without this unique skill, all your other training can be rendered useless. Many of the exercises are easy to perform and do not require expensive equipment.

Mental and Emotional Skills Training

We introduce mental and emotional skills training to help players deal with both success and failure, as well as to deal with game pressure. Baseball is unique in that being successful three times out of ten gets you to the Hall of Fame. Players have to deal with consistent failure and still remain confident.

The following are the basics for a Baseball / Softball Conditioning Workout:

Cardiovascular Training: Sprints and interval training, not long distance running

Stretching: Important for increased flexibility and injury prevention.

Strength Training: Important for increased maximum strength. Begin with bodyweight exercises and progress to weights.

Medicine Ball Exercises: Important for rapid powerful upper body movements to develop increased explosiveness and rotational forces.

Plyometrics: Used in conjunction with strength development in an integrated program to improve the link between the strength developed in the weight room and the ability to develop explosive power, speed and agility.

Speed, Agility and Quickness Training: When it comes to baseball, speed and agility are important on both sides of the field. Speed is important in the field where hit balls must be defended. On offense, speed puts pressure on the other team and distracts the pitcher and catcher; this help the hitter get better pitches to hit. The development of speed and agility is as vital as the development of batting power and throwing arm stability.

When you translate the strength developed in the weight room with the speed developed during the plyometric training and then add proper batting and pitching mechanics, you will have a stronger, more powerful, more productive player.

All training needs to be integrated with sports skill training. You cannot do either area in isolation without leaving the player's development lacking. Trainers need to work closely with the team coach and medical staff to ensure a balanced, effective training program. Nutrition and diet and various recovery methods should be discussed with appropriate professionals in those fields.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

Charles Slavik is the President of the Eagle Baseball Club in South Elgin, Illinois. Coach Slavik has helped his players' maximize their athletic performance and avoid injuries by combining his 16 years of experience as a youth baseball & softball coach with his advanced and practical knowledge of the strength and conditioning field. Charles is a Certified Personal Trainer by the National Strength and Conditioning Association and a member of the American Baseball Coaches Association.

Speed Improvement Drills

The Mach drills are examples of things that can be done as part of a dynamic warm-up in lieu of static stretching before throwing.

Static stretching of cold muscles is at best virtually useless and at worst harmful, IMO and backed by research.

Static Stretching after the core ( body temperature ) is raised, please. That includes the bands work.

Cariocas are an excellent, baseball-relevant warm-up exercise in that they emphasize the counter-rotation or separation ( one half goes one direction the other half opposes), of the upper and lower body. This is KEY. The kids that get this right advance on the big field, the others don't and wonder why. It's one of the keys to generating power and force to the ball or the bat. I don't have an illustration but you can YouTube cariocas and see a demonstration.

The start mechanics are very key for baseball. Getting good jumps improves hitter, fielders, base runners. Starts in baseball are initiated by visual stimuli rather than starters gun, so drills would be built around reading pitchers moves ( go forward or go back, taking leads and getting good jumps ). Baseball starts are from standing (OF) , crouching (IF) or sideways ( base runner ) positions rather than from starters blocks ( like track ) but the runner that gets in the optimal mechanical positions ( as illustrated in the pictures) best wins.

SPRINT, SPRINT, SPRINT over long distance running in your program by a lot. Pitchers can do some poles after they throw, but improvements in 1-10 yard speed, 1-30 yard speed (home to first) and 1-60 yard speed (home to second) will win you your fair share of games. If you want to occasionally go 1-90 yards ( triples ) for endurance, great. That's fairly long-distance for BB players.

However many times you run them 1-90, I would probably distribute about 2x as many 1-60's, 2x as many 1-30's as 1-60's ( 4x the # of 1-90's ) and so on. Build your house on a foundation of sprinting, and finish the top floor with some endurance work, rather than the other way around.

Hope this helps. - CS

Speed-Strength Training Basics: Tips for All Athletes from All Sports

APRIL 16, 2011 BY

----

Pitching Mechanics

First Stage of the Delivery:

I like his leg lift and initial inward turn. He gets pretty good counter rotation. Knee comes up to hip level and pointed closer to SS than 3B position.

As he gets bigger, stronger and more flexible, he should get more in both categories.

This will help him us his lower half to provide power and protect him from arm injury.

The model he should most try to emulate is Lincecum. What allows Lincecum to do the things he does IMO is his great flexibility and his "relative" strength.

He's gymnast strong or strong relative to his height / weight. He's also pretty close to gymnast flexible, which is rare.

It's also why a lot of folks who want to emulate the Lincecum long stride (it's all the rage) without first having the Lincecum hyper-flexibility are getting on the entrance ramp for the pulled hamstring / pulled groin superhighway. Don't put the cart before the horse - form follows function.

Here's an example of Lincecum's pre-game stretching routine. This is pretty good stuff.

Tim Lincecum Pre-Game Stretching Routine

Last Stage of the Delivery (finish / follow-through):

I'm going to skip from the first stage of the delivery to the third, the finish / follow through is pretty good. I'd like to see a more aggressive push off the rubber and a more aggressive follow-through ( 180 degrees of rotation - Pitching shoulder begins pointing to 2B in the stretch and ends pointing at Home Plate ).

When this happens - either a more aggressive push off the rubber from balance point and/ or front-side glove pull through - you'll see more arm speed -> more ball velocity on FB. When the back leg kick is higher than his head in follow-through, you'll know he's doing it fine. The 180 degrees of rotation give pitcher a simple set of checkpoints to maintain control while they are adding velocity, so we aren't trading one off in pursuit of the other (common for this age).

The Lincecum slow-motion clips and .gifs below show and the authors describe what should be happening.

I could watch this over and over and over. And if I was still pitching, I think I would.

Tim Lincecum Slow-Motion

The videos are more for the pitcher ( to visualize proper mechanics ), the authors descriptions are more for the coach (and you and your husband are ultimately his coach).

Pitchers should see, visualize and execute the model they are trying to achieve.

Coaches should understand the underlying nuts-and-bolts for assessing and correcting (tinkering).

The Second Stage (arm action):

This is the area we need to concentrate on the most. He kind of drifts through this and loses some of the benefits of the good start of the delivery and the good finish.

The purpose of the arm action is to put the arm in the best position to throw. After the hands break, a down-back-and-up arm action while the his body falls forward towards the plate provides a nice pre-stretch that will generate better arm speed. Lincecum makes a very aggressive stick down, then you see the ball point towards 2B (the base not the player) and then up.

By then you should have the push off the rubber, the aggressive turn of the hips which turns the chest / torso so the arm can whip through and deliver the ball.

I like these Trevor Bauer pics for illustration.

Anyway, have fun with this. If you have any questions ( I know it seems like a lot of stuff ) let me know. I tried to keep it as simple as possible, but it really doesn't lend itself to simplicity if you're going to do it right.

----------------------

Update 9/1/2010

As I discuss in more detail lower down on the page, for a few years I have been concerned about the long-term health of Tim Lincecum's arm. I believe that these concerns are related to the struggles that Tim Lincecum has experienced lately. The problem is that Tim Lincecum has an Inverted L in his arm action, and a timing problem, as the video clip below demonstrates.

Tim Lincecum

The Inverted L is clearly visible in Frame 25. Notice how he picks his Pitching Arm Side (PAS) elbow straight up out of the plunged, ball by the PAS hip position. The problem is that this creates a timing problem. In Frame 26, when Tim Lincecum's Glove Side (GS) foot plants, his pitching arm is late and isn't close to vertical. This causes his PAS upper arm to externally rotate 100 or more degrees by Frame 27, which puts a lot of strain on both the elbow and the shoulder.

12/1/2008

I recently came across some super slow motion video of Tim Lincecum that makes clear some of the things I think he does well, but also makes me more concerned about the long-term health of his arm.

Let me explain why I say that.

Let me explain why I say that.

Tim Lincecum - Super Slow Motion

In Frame 18 you can see how Tim Lincecum does three things that are good. First, he drives off the rubber toward the plate with his Pitching Arm Side (PAS) leg. Second, he sweeps his leg out toward Third Base and into foot plant, which is something that great pitchers like Greg Maddux do and I prefer to a more linear stride like Mark Prior's. Third, he leads his stride with his Glove Side (GS) butt cheek.

In Frame 80, you can also see something that is good. Notice how he leads with his PAS hand, rather than his PAS elbow, as he comes out of the "plunged" position with his PAS hand behind his PAS butt cheek. This keeps him from getting into the Inverted W position (although he does show some Inverted L).

Frame 92 is when I start seeing things that make me nervous. The thing to notice is that Tim Lincecum's GS foot has planted but his PAS forearm is only horizontal. Given that, as is typical, his shoulders start to rotate at this moment, this means that his PAS upper arm will externally rotate especially much and hard. This can significantly increase the load on both the elbow and the shoulder.

In Frame 80, you can also see something that is good. Notice how he leads with his PAS hand, rather than his PAS elbow, as he comes out of the "plunged" position with his PAS hand behind his PAS butt cheek. This keeps him from getting into the Inverted W position (although he does show some Inverted L).

Frame 92 is when I start seeing things that make me nervous. The thing to notice is that Tim Lincecum's GS foot has planted but his PAS forearm is only horizontal. Given that, as is typical, his shoulders start to rotate at this moment, this means that his PAS upper arm will externally rotate especially much and hard. This can significantly increase the load on both the elbow and the shoulder.

Lincecum's Hip/Shoulder Separation

In Frame 110, you can see Tim Lincecum's best-in-the-world hip/shoulder separation. Notice how, as in the still photo above, Tim Lincecum's belt buckle is pointing at Home Plate while his shoulders are still closed and facing Third Base. In this frame, Tim Lincecum's shoulders have already rotated 15 or degrees and his PAS forearm is vertical (with respect to his upper spine) and in the high-cocked position.

In Frame 110, you can see Tim Lincecum's best-in-the-world hip/shoulder separation. Notice how, as in the still photo above, Tim Lincecum's belt buckle is pointing at Home Plate while his shoulders are still closed and facing Third Base. In this frame, Tim Lincecum's shoulders have already rotated 15 or degrees and his PAS forearm is vertical (with respect to his upper spine) and in the high-cocked position.

Finally, Frame 152 shows that Tim Lincecum extends his GS knee through the release point. While this can help to boost a pitcher's velocity, I'm not a fan of this because I know it can lead to knee and hip problems and think it can increase the load on the elbow and the shoulder.

Arm Action And Timing

12/12/2007

A pitcher's arm action and timing are the primary determinants of the long-term health of their arm, so it's always the first thing I look at. Tim Lincecum's arm action is mostly good, as the clip below demonstrates.

Tim Lincecum

Tim Lincecum has a plunge, out, and up arm action that bears some resemblance to that of Greg Maddux. However, Tim Lincecum's Pitching Arm Side (aka PAS) elbow gets higher than does Greg Maddux's; it almost reaches the level of his shoulders, which makes me a little nervous. At least Tim Lincecum's PAS elbow drops as his shoulders turn, which his good.

---------

In Search of the Perfect Arm Action -- Part 2

In case you missed it, here is part one of the series "In Search of the Perfect Arm Action". The gist of the article boils down to this (and skip this part if you already read part one):

Chris O'Leary's definition of the elbow picking up the ball is much too narrow - he sees it as a reason pitchers get into the Inverted L and W positions and sees it as a quality only in the arm actions of pitchers like B.J. Ryan:

"A better definition of the elbow picking up the ball is that the elbow stays above the level of the hand and the ball until just before the shoulders start to rotate, as you see in the arm action of BJ Ryan (who has arm problems as a result of his arm action)"

My response: Letting the elbow pick up the ball is not why pitchers get into an Inverted L and W position. You can get into an Inverted L and W position but it doesn't mean pitchers will get into that position.

This is what I left off with:

I interpret the "elbow picking up the ball" to mean the ball never getting higher than the elbow until just before the elbow rotates (about 4 or 5 frames before foot plant)...While I can continue to describe in writing what the elbow picking up the ball means"

We're going to truly see what the "elbow picking up the ball" means and the different ways to do so as well as determine if there is one right way to do it. Let's first take note of Nolan Ryan, a pitcher O'Leary likes to use as an example of good mechanics (and rightly so):

Nolan Ryan letting the elbow pick up the ball

I think it's pretty easy to see the ball does not "pick up the elbow"; it's the other way around. Ryan is letting the elbow pick up the ball until just before his elbow rotates to a ready-to-throw position. Yes, he reaches a cocked position with his arm very qucikly, but that does not mean the elbow is not pickng up the ball.

Another pitcher, Yovani Gallardo (who I profiled earlier this year), also lets the elbow pick up the ball:

Gallardo's pitching mechanics" style="margin-top:0px;margin-right:0px;margin-bottom:0px;margin-left:0px;vertical-align:baseline;">

Yovani Gallardo letting the elbow pick up the ball

*Note - you can ignore the numbers that pop up in this animation

Though the angles are obviously different, you can still see some of the differences between the arm actions. Gallardo straightens his arm out a little more than Ryan who maintains a slight bend in his arm (which I prefer). Ryan is also faster in getting his arm into a ready-to-throw position than Gallardo, but one similarity they both possess is letting the elbow pick up the ball and never getting into an Inverted L or W position, while the ball never goes above the elbow until about 4 or 5 frames before foot plant, just before the elbow begins to rotate.

For a contrast to the elbow picking up the ball, I used Jeff Manship as an example of a pitcher allowing the ball to pick up the elbow. I went back to find a better graphic of Manship to use than in my previous article and came up with this:

Jeff Manship letting the ball pick up the elbow

One thing I don't like about Manship's arm action is the way his arm rises through his arm circle. See how the forearm, wrist, and ball rise up, leaving the elbow relatively on the same plane (though it does rise a little)? This kind of arm action makes it harder for the arm to produce velocity because you're making it more difficult to "scap load".

Scap loading is a major proponent in producing velocity. This is the horizontal loading of the arm, meaning the arm is loaded toward first (if the pitcher is right handed) instead of back toward second base. You have all these elastic muscles and tendons in the shoulder and by loading the arm horizontally, you create tension in these muscles, creating a large amount of kinetic energy ready to be unloaded forward. If done effciently (and I can't emphasize this enough), scap loading can help a pitcher improve velociy. I'll go a little more in-depth on this topic in the near future.

However, the bigger reason Manship's arm action gives me pause is the fact he cocks his wrist as he moves through his wind-up. You can see this here:

That straight line that you should be able to draw from his elbow to his wrist/ball can't be drawn anymore because the ball ends up above that line. I've said Manship's arm action more resembles Rich Harden, but I've concluded Harden's mechanics are more aggressive and more risky than Manship after a couple more looks at Harden.

O'Leary goes on to say this:

"Video clips of Greg Maddux, who is one of the most durable pitchers in history, show that he also doesn't pick up the ball with his elbow. Instead, his elbow always stays quite low, and his PAS hand quickly gets above the level of his elbow, during his arm swing."

Ya know, I can go along with this. When you watch Maddux, his elbow doesn't really pick up the ball, but again I go to my point of being able to draw a straight line, from elbow to wrist to ball and we'll use the animation O'Leary provides to illustrate this point:

Greg Maddux pitching mechanics

O'Leary is right that in that he keeps his elbow quite low and he really doesn't lift the ball with his elbow. However, I disagree with this part of what O'Leary says:

"First, because Jeff Manship's forearm is intact, and not broken or missing the Radius and Ulna bones, you can of course draw a straight line from his elbow to his wrist. Second, the arm action you see in the clip above is actually good and resembles the arm action of Greg Maddux and Roger Clemens (which of course is a good thing)."

What do you think? Below, I provide the arm actions of Clemens and use the Manship graphic from above: compare all three and make a determination:

Do you think the arm actions of Maddux and Clemens resemble Manship's? I don't. The differences?

The path their arms take as they work their way through the wind-up. The elbow rotation. The relative noise of each pitcher's arm as they make their way through the wind-up. By this I mean you can see how quiet Maddux's and Clemens' arms stay until just before elbow rotation. It's as if Maddux is floating his arm before elbow rotation, while Clemens keeps his arm stiff, not allowing for any unnecessary movements.

To sum this up, Clemens and Maddux don't let the "elbow pick up the ball" as much as somebody like Nolan Ryan, but they do not maintain an arm action that lets the ball pick up the elbow nor do they resemeble Manship's arm action.

The last guy O'Leary used was Roy Oswalt:

"...Roy Oswalt doesn't pick up the ball with his elbow. That's why I like his arm action. Instead, as you can plainly see, the ball gets up to the level of Roy Oswalt's elbow relatively quickly and then goes above it a couple of frames before his shoulders start to rotate."

Roy Oswalt pitching mechanics

The graphic is kind of grainy and much of his arm disappears behind his body, but the first thing you notice is the horizontal loading of the arm (see how the line does not move left, but simply moves backward?). Secondly, I would venture to say the elbow does pick up the ball, but O'Leary is right in that Oswalt gets the ball up to his elbow relatively quickly. However, that is simply because Oswalt's arm is so fast and hitch free, with little loss of momentum through his arm circle. In addition, Oswalt breaks his hands with intent. The ball reaches the level of the elbow just before his elbow is about to rotate; nothing abnormal about that. And again I'll point out Oswalt's arm action does not resemble Manship's.

The important thing to point out is that arm actions come in many forms and not any one arm action is correct. However, you'll notice all the arm actions displayed in this article are different than Manship's arm action.

So does that mean Manship is destined for injury? I think Manship's risk of injury is heightened somewhat though how much I don't know. Of course, I'm also factoring in the fact that Manship has a history of arm problems and has already undergone Tommy John surgery once before.

It should also be said Manship is a pitcher I would have no problem taking on my team. His control is excellent (notice how he firms his glove up as his front shoulder is about to open), his curveball is a plus pitch, he generates ground balls, and he strikes a healthy percentage of the batters he faces.

So that leads to the question: if you encounter somebody with an arm action you deem risky, should you go about changing it and should you try to make a player "emulate" other pitchers or let them be themselves? I'll address this in my next article for this series.

Best Hitting Articles of All Time (BHAAT)

NYT: Hitting a Baseball: So Much to Do, So Little Time (from March 27,1994)

THE SCIENCE OF THE SWING - Dr. Robert Adair, Yale University

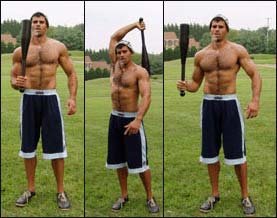

Favorite Clubbell Exercises for Baseball

Coach

Would you post your top 5 clubbell exercise

Would you post your top 5 clubbell exercise

Posted by Greg to The Slav's Baseball Blog - BASEBALL 24-7-365 at 3/17/2013 12:52 PM

Hope this helps, Greg. If you have any further questions, please don't hesitate to ask.

I personally own (2) each of the 5lb. and 10 lb clubbells. I bought them back in 2002. I have Scott Sonnon's book "Clubbell Training for Circular Strength" - An Ancient Tool for the Modern Athlete" and the VHS tape Olympic Clubbell Swinging. We have used the clubbells for personal training and private training for baseball and softball for both pitchers and hitters.

Overall, I would say Armpit Cast, Parry Cast, Shield Cast, Shoulder Cast, Wrist Cast and Hammer Throw. Sorry, that's six!! With Youth to HS players there is not much as much of a distinction between a hitters vs. pitchers workout, but to break them out separately:

Pitchers Hitters

Armpit Cast Armpit Cast

Shield Cast Parry Cast

Shoulder Cast Hammer Throw

Wrist Cast Wrist Cast

Progressing to Pendulum Cast and the Mill routine. Some illustrations and descriptions are provided below from Scott's site and some other sources I find pretty reliable:

In the interest of full disclosure, I have provided personal testimonials for the Clubbells on Scott's rmaxinternationl.com site back in 2003.

"Thanks. We love the Clubbells™ for baseball training for both pitchers and hitters. I have the Clubbell Training for Circular Strength book, video and the 5 and 10 pound size clubbells. The exercise program works well for developing grip strength and rotational power both of which are vital for baseball players." - Charles Slavik, NSCA-CPT, ISSA-YFT President, Eagle Baseball Club, LLC Tampa Bay's Finest Baseball & Softball Training

"Thanks. We love the Clubbells for baseball training for both pitchers and hitters. The exercise program works well for developing grip strength and rotational power both of which are vital for baseball players." - Charles Slavik, NSCA-CPT, ISSA-YFT President, Eagle Baseball Club, LLC Tampa Bay's Finest Baseball & Softball Training (Tampa, FL, USA)

Baseball players benefit greatly from the rotational/angular strength development. Anything from sledgehammers to wood-chopping to heavy medicine balls may transfer over... and of course, especially Clubbells.

Check out Amazon.com for the book - "Clubbell Training for Circular Strength." Get it before Clubbells to make sure they're what you want and need. Then confirm it with your coach to prevent any overtraining potential.

CORE EXERCISES:

- Swing: the core cardio competency of designed to teach the 7 Key Components of CST Form.

- ** Arm Cast: the arm-god guaranteed to give you the extreme shoulder range of motion strength of Atlas.

- ** Pendulum (Forward and Side): promises the ability to absorb and retranslate shock with the agility of a professional football lineman.

- ** Shield Cast: the angular / diagonal strength of weapon wielding warriors for developing flexible but granite strong shoulders, arms and lats.

- ** Shoulder Cast: for a John Henry sledgehammer strong back, arms and core, this targets the rare but critical lateral power.

- ** Parry Cast (Forward and Reverse): the most unique development of rotary reactive strength to develop spring steel strong tendons throughout the body.

COMBO ROUTINES

- Swipe: the ultimate three-dimensional metabolic conditioning engine to give you the tremendously powerful back, glutes and legs which has made wrestlers renown!

- ** Mill: the greatest multi-planar endurance challenge ever created which will develop the tree-swinging traps, shoulders and lats to make a gorilla proud!

- ** Hammer Swing: the most superior core activation exercise on the planet, guaranteed to give you an molten iron core which of a volcano!

Indy Ishaya's Article:

Armpit casts 3-5 sets of 3-5 reps.

Wrist casts 2-5 sets of 1-3 reps.

Inward Pendulums with a side lunge 5 sets of 10-25 reps. Begin by performing the pendulum, and as the weight passes to outside your body, step out with the same side leg into a lunge, ending the pendulum in order. Reverse the motion using an outward pendulum to end standing upright and holding the 'bell in order.

Mike Mahler's Article:

Clubbell Drills

Pendulum - View

Clean one Clubbell to order and swing it down and out to the left making a half circle. Catch the Clubbell and then swing it in the opposite direction and catch it again. Go back and forth with each arm for 10 repetitions. This is a great drill for loosening up the shoulders before and after workouts.

This is my favorite Clubbell drill and I noticed the increased stability in my shoulders after a few sessions of executing the Arm-Pit Cast. Clean a Clubbell to order and then raise your elbow above your head and take the Clubbell all the way around and bring it back to the starting position. This move had a real primal feel to it and requires a good amount of coordination. Go light and ease into it to avoid hitting yourself in the face. Do a few sets of 5-10 per workout.

Double Arm-Pit Cast - View

This exercise really hits the rear delts and a few muscles that you did not even realize that you had. I experienced a noticeable increase in shoulder size especially the rear delts after doing this exercise for only a week. Similar to the single Arm-pit Cast, this exercise is also great for shoulder stability. While it is not a triceps exercise, I found that this exercise really pumped up my triceps. Clean two Clubbells to order. Crush grip the handles and take the Clubbells behind your head in right angles. Contract your stomach and butt and bring the Clubbells back to the starting position. try doing a few sets of 5-10 reps.

Arm Cast

This excersise for the entire upper body. Especially strong is the load on the broadest muscles of your back(latissimus dorsi), Abs, and the muscles of the forearm and hand.

You can run with any kind of clubs. In order not to injury joints -start with light weights. This council will be entitled to any type ofexercise.

You can run with any kind of clubs. In order not to injury joints -start with light weights. This council will be entitled to any type ofexercise.

Difficulty of exercise: Middle

Purpose of exercise: Endurance, Strength

Working muscles

You can click on muscle to view another routines for it.

Stages

Clubbell mill

Whole body exercise. 5x20rep works well with clubbell of medium weight(16 lbs clubbell weight for 176 lbs man weight appr.) Use your torso to move the weight. From torso you develop maximum impulse for this movement.

Switch from one hand to another during execution. One touch for one hand and instead of rest do exercise another hand.

You can choose another variant of training though.

Great exercise for punchers, strikers and grapplers.

Difficulty of exercise: Middle

Purpose of exercise: Strength, Coordination, Explosive Strength

You can do it with: Indian Club Clubbells (Sonnon)

Working muscles

You can click on muscle to view another routines for it.

Stages

1 comment:

Coach

Would you post your top 5 clubbell exercise

Post a Comment