It beats the living daylights out of what we've been doing for a couple of generations!!

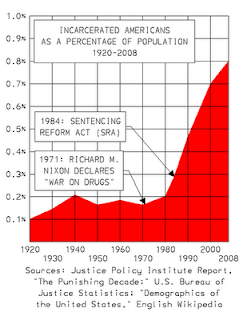

The War is unwinnable, unsustainable, untenable, unconscionable by itself and it fosters the other inequitable injustices that flow from it. All you have to do is look at our prison population numbers and composition to see that.

Oh, that's right!! We don't want to see that. "Honey. Let's round up the kids and go to the county prison, see where are tax dollars are going". Said no taxpayer, EVER!!

Time to take a look at what we are doing and why.

Not sure if I feel any safer now with 0.8% of the population in prison than pre-war, pre-Nixon days when 0.2% of the population was in prison. If you want to go the race route, I don't feel any safer next to a meth-head than a crack-head. But the justice system treats them different. Needs to be fixed.

The residual benefit IMO would be a reduction in violent crime in general and gun crime in particular. Then maybe the Second Amendment can breathe a little easier.

Next front, The War on Poverty.

The Economics Behind the U.S. Government's Unwinnable War on Drugs

http://www.econlib.org/library/Columns/y2013/Powelldrugs.html---ConclusionThe U.S. government's policy of drug prohibition, like alcohol prohibition before it, is a failure—and not one that can be corrected by a mere tweaking of current policy. The economic analysis of fighting a supply-side drug war predicts that the war will enhance drug suppliers' revenues, enabling them to continuously ratchet up their efforts to supply drugs in response to greater enforcement. The result is a drug war that escalates in cost and violence.

Furthermore, the secondary consequences of prohibition are perverse. The drug war causes drugs to be more potent and their quality less predictable than if drugs were legal, leaving the remaining users at greater risk and, in the face of higher prices, more likely to commit crimes to support their habit.

In short, the means—drug prohibition—is incompatible with the ends of improving health and decreasing violence. There are two paths forward: a demand-side drug war or legalization.

A demand-side drug war that places draconian penalties on usage or possession does not necessarily fail a means-ends test. If the goal is simply to end drug usage, implementing a swift death penalty for anyone convicted of possession or use would do the trick. Of course, it would not improve those people's health. Most people, including myself, would consider such a policy even more unjust than the current drug policy.

The alternative, legalization, is a better path forward. It passes a means-ends test while better respecting individual liberty. Consumption may increase but the drugs that are consumed would be safer; and violence would decrease. To the extent that decreasing drug consumption is desirable, moral suasion and education would be more effective—without the nasty side effects—than the current policy of prohibition.

Pettit on the Prison Population, Survey Data and African-American Progress

Becky Pettit

Hosted by Russ Roberts

http://www.econtalk.org/archives/2012/12/pettit_on_the_p.htmlBecky Pettit of the University of Washington and author of Invisible Men talks with EconTalk host Russ Roberts about the growth of the prison population in the United States in recent decades. Pettit describes the magnitude of the increase particularly among demographic groups. She then discusses the implications of this increase for interpreting social statistics. Because the prison population isn't included in the main government surveys used by social scientists, data drawn from those surveys can be misleading as to what is actually happening among demographic groups, particularly the African-American population.

Highlights

| Time | |

|---|---|

| 0:33 | Intro. [Recording date: December 17, 2012.] Russ: Your book is about the growth of the prison and jail population in America, its impact on people's lives, and how it affects our understanding of social statistics. Let's start with some basic facts. What has happened to the prison population in the United States over the last 30 or 40 years? Guest: Over the last 35 years the prison population has quintupled. We now have approximately 2.3 million Americans who are in prisons or jails on any given day. That number has been about the same for the last 4 years. So, after several decades of an increase we have leveled off at about 2.3 million. And one of the key features of that growth in incarceration, most scholars agree that the growth was largely driven by shifts in policing, prosecution, and sentencing. Almost half of offenders are in prison or jail for nonviolent drug or property crimes. And one of the key things that's happening over time is that the risk of incarceration has become increasingly concentrated among those with very low levels of education. So over half of inmates, young inmates between 20 and 35, have less than a high school diploma. Russ: And is that a new phenomenon, and if so, relative to say what time period? Because my impression is that crime is concentrated among both young and male folks. So it wouldn't surprise me that a disproportionate share of the prison population is young and male, especially due to that increase, if it's due to nonviolent crimes. Guest: Yeah. So, if we put this in a longer historical perspective, we've been collecting fairly reliable data on the inmate population since about 1925. And from 1925 to about the early 1970s the prison population was very stable and at about 1 tenth of one percent of the population. Russ: That's 100 per 100,000. Guest: Yeah, that's about right. Russ: That's the number that is evidently commonly used--per hundred thousand. Guest: That's right. And what's happened over the last 35 years or so is that there's been this dramatic increase so that by 2008 that number was about 750 per 100,000. Russ: Massive increase. Guest: Massive increase. And one of the other things: one number that floats around a lot. If we think about it as a fraction of the adult population, those over age 18, it's 1 in 100. One in one hundred American adults is in prison or jail on any given day. If we include people who are under other forms of justice supervision, it's 1 in 31. Russ: Wait a minute. One in 31--meaning 3%? Guest: Yes. Three percent of the adult population. Russ: Roughly 3% of the United States are either in prison or jail or--what was the third category? Guest: Under the supervision of the criminal justice system. Probation, parole. And it is historically unique. It is also comparatively unique. The United States has a higher fraction of its population incarcerated than any other advanced industrialized country. By quite a lot. But one of the key issues has been that for a long time there has been a very huge gender and race disproportionality in incarceration. Men are much more likely to be in prison or jail than are women. African-Americans are much more likely to be in prison or jail than are whites. Or Hispanics. Or any other racial group. And people with low levels of education have historically been overrepresented in the criminal justice system, but that has increased quite dramatically over the last 35 years. And it's not surprising if you think about the kinds of crimes and activity that now carry with them custodial sentences. Crimes that may be motivated as much by economic reasons as anything else. And thinking about drug sales and property offenses and other things that 35 years ago people, even if they were caught and convicted, they weren't put in prison or jail, typically. Prison and jail were reserved for primarily very violent offenses. So there's been this real dramatic shift. There is still gender inequality in incarceration; there is still racial inequality in incarceration; and there is still educational inequality. And one of the key features from my work--and this is important in the context of my new book--is that educational inequality has become so dramatic that among young black men who have dropped out of high school, a huge fraction of them, upwards of 2/3, can expect to spend at least a year in prison. Russ: That's an extraordinary number. |

| 6:38 | Russ: Let me ask you about one of the challenges of these data and one of the things you learn from reading your book, which has nothing to do with prisons particularly. Prisons are an example of it, but defining data and ratios is tricky in social science. So when you talk about the prison population, does that mean part year, full year, any one day? And you just gave a number, the way you described it, which is I think one of the ends of one of the assumptions you can make, is on a particular day--today--and we don't literally have a count. We don't have a census of, a literal census--it's an estimate in some dimension. But on any particular day, I think you said that 1 in 31 number, over 3%--is on any particular day, right? So, another way to measure it would be how many people are in prison or in jail or under the supervision of the justice system for the entire calendar year of, say, 2011. Do the numbers get broken down in those ways, or are we always trying to kind of guesstimate what the size of the population is? I mean, just like we have for any population number. Obviously people live and die, people move; they immigrate, they emigrate. People go in and out of prison and jail, sometimes multiple times, I assume, in a year even.Guest: Sure. Russ: One of the challenges is just methodological here.Guest: Yeah. So, when we hear a number like there are 2.3 million Americans in prison or jail, that's a point-in-time estimate. And the Bureau of Justice statistics does a census of facilities, and it varies depending on the facility. Usually once a year, in July or in December. And so those numbers are essentially head counts--who is in on a given day. We can also think about--and that's the stock of inmates. Guest: And seasonal. Right? So, it's November, it's a particular time of year, for whatever it's worth. Guest: Sure. It is seasonal. And one of the things that we had observed over the long buildup from the early 1970s through the late first decade of the 2000s was that year on year there was growth. So, even though there might be some seasonality, there was still year on year growth. And that's one of the things that we have seen really in these last four years--we've seen leveling overall, nationwide. And much of that is being driven by certain states where we are seeing actual declines in some states. So, for example, New York is seeing some declines. And I think one of the primary explanations for that is New York is moving to a whole range of what we think of as diversions, alternatives to correctional sentences, drug courts, and the like. Also the state of California is seeing some declines. And some of that is due to the Plata Decision-- Russ: Which is what? Guest: Which is the Supreme Court decision that essentially ruled that California inmates were not receiving adequate health care and inmates in correctional facilities have a Constitutionally protected right to health care. And the overcrowding in California prisons was so extreme that inmates were essentially not receiving adequate treatment. And punishment was deemed cruel and unusual, I believe. And so the state was mandated to reduce their prison population. And they've done a number of things in order to accomplish that. But what we're seeing is that statewide there has actually been a decline in inmates. But still, at the national level we see this 2.3 million number. And it's been pretty stable for the last 4 years. Now clearly inmates cycle through. And jails are typically county-run or at the county level and they house inmates who are either awaiting trial or who have a sentence of less than a year. State and Federal facilities typically hold inmates that have been convicted and their sentence is longer than a year. So at the jail level we see huge numbers of people cycle through. So, people say, there are 12 million visits to local jails. On any given day--I can't remember the number exactly--but it's about 800,000. About 3/4 of a million people. But over the course of a year, there are 12 million visits, and if we factor out the people who go through more than once, then it's about 9 million people. Nine million individuals spend at least some time in jail. Prisons, because by definition people are there longer, there's less cycling. But estimates suggest that about 3/4 of a million people are released from prison over the course of a year. 700,000. And so these are clearly--my work focuses on people when they are incarcerated. But this is something that we've talked quite a lot about, publically, re-entry programs, things like the Second Chance Act, which was designed to increase public investments in training and education for people who are being released, because the vast majority of inmates in both local facilities as well as in state and federal prisons do get released. Estimate suggest about 95%. So at some point most people who have spent some time in prison or jail will get out. |

| 13:34 | Russ: Yeah. There's a weird--to me, maybe not other people--interaction between, say, prison labor and non-prison labor. People don't like prison labor. It "competes" with non-prison labor. But of course we all compete with each other. It's a weird thing, to me. But then you have this idea of training. It seems like a good idea to do something to train people so when they get out they don't become prisoners again. And yet I think there's some opposition to that, that somehow either they "don't deserve it," or it's competing with honest people's labor. There's a lot of political tension there, right? Guest: Oh, absolutely. I think that the prison system--and I mean that to encompass federal, state, and local facilities--when we think about the prison system or the criminal justice system, if we go back to the 1940s or 1950s or the 1960s there was much more of a rehabilitative philosophy, and the idea that people committed crimes; they spent some time in prison or jail; paid their debt to society; hopefully emerged on the other side better prepared to participate. And that might have involved some rehabilitation while incarcerated, in some kind of job training or educational program. And many of those programs persist in facilities. However, in the context of this massive increase in incarceration the amount of money we can devote to rehabilitative programs, in contrast to just supervision, is dwindling, given the per-person who are incarcerated. Spending on prisons has gone up, but there are a number of things that demand lots of resources: supervision, increases in solitary confinement, the aging of prison facilities, the aging of inmates themselves, the health care needs of inmates. And so there's less and less available per person for education and training and things like that. Russ: Basically you are running a hotel for 2.3 million people--it's a 2.3 million person hotel chain. The TVs aren't as large and as numerous, the beds aren't as comfortable, there's less marble in the bathroom. But it's expensive, obviously. Guest: It is very expensive. So this is one of the issues that a number of states have wrestled with in the economic downturn of the last 200s, is that they have very few state resources to devote to a whole range of things. Prison facilities are one of them. And so states have found themselves cutting back. And there are a couple of ways to limit prison costs. One is to limit the number of inmates. And another is to limit the services that they receive while they are incarcerated. Russ: Right. Well, based on your earlier remark on the reductions in California and New York, I bet they are doing a little bit of everything. Guest: Yeah. |

| 16:46 | Russ: The question I want to ask is: Given this growth, the challenge of this field obviously is that there is an incredibly complicated interplay between crime, policing, and sentencing. Right? They are all changing over time. And so when we look at this big increase of manifold, multiple number in inmates, people incarcerated, it could be due to all three of those factors getting more serious. Crime rates could be increasing; policing could be more intense; and sentencing could be longer. Or, it could be: Crime rates are about the same but we catch more criminals and just keep them in jail longer. Do we know anything about that breakdown of those three factors? And in particular, given that from what you say it's largely an increase in--I don't know what the technical term is--non-violent crime, drug users, etc., which of course has some violence related to it for other reasons: do we know how much of this increase is due to changes in crime or policing or sentencing? I know people make different claims because they have a stake in it, most claims. Do we know anything reliable about that? Guest: Yeah. The evidence is pretty clear. The crime rate is down to levels we haven't seen since the late 1960s. So, crime is way down from its historic heights. This is true no matter what indicator you look at. You can look at murders, you can look at violent crime, you can look at property crime--any range of them. There clearly were peaks in the crime rate in the early 1980s, in the early 1990s, depending on what measure you looked at. But now crime is down, way down. The evidence suggests, depending on what crime you look at specifically, there was an increase between last year and this--2010-2011. But it's a pretty small increase on a low level to begin with. So I think most scholars agree that the buildup of the criminal justice system, and certainly the maintenance at the level that it is now, is not about crime, or certainly not for the last almost 20 years, increases in crime, because crime hasn't been increasing. And instead it has to do with some of the other things that you mentioned, which is increased policing and surveillance; and when people then are arrested, there's increasing prosecution. Now that doesn't necessarily mean people are going to trial. It means they may be plea-bargaining. There's a range of other ways to resolve these cases. And then there are mandatory minimum sentences. And so those mandatory minimum sentences require that people spend some time in prison or jail. Now, some states are clearly experimenting with diversions or alternatives to custodial sentences where people may engage in drug court. It may be a drug-related offense and they may receive drug treatment as sort of a resolution. They may receive community-based supervision, some kind of a probationary sentence. So, there are movements, and I think these are as fiscally driven as anything else, as far as I can tell. It's not an area I study, but from what I understand. And I think one of the other things that's really driving the increase--and this is particularly acute in some states like California--are parole revocations. Where, it's not necessarily, someone may have been released on parole and they may not even have committed a new offense; but they may be in violation of parole. And there are lots of ways people can violate parole. They can not show up for their meeting with a parole officer or not update their address; have a dirty drug test. And there's a whole range of things that can lead to a parole revocation, where someone will then go back into prison. And then for a longer period of time. It's been shown in some states, California in particular, to really swell the ranks of those incarcerated. So it's not just that they are having, getting mandatory minimums, but then they are actually having to serve the full extent of the sentence; and potentially longer. |

| 21:57 | Russ: Well coming back to our earlier point--a lot of people argue that the crime-prison relationship runs in the opposite direction: that because we've imprisoned so many people, the crime rate is lower. One view is: with crimes falling, why are we having so many people in prison? And some people say: Because causation runs the other direction; we've imprisoned a lot of people; we've given up on rehabilitation; we've said the best way to keep people from being criminals is we'll keep them in prison and we'll lock them up. Not a very attractive, pleasant viewpoint, but it might be true. It certainly reduces repeat offenses if you are in jail. So, is there any reliable--I'm sure there isn't, but I'll ask anyway because I'm polite--evidence that disentangles that causation problem? It's obviously a tricky thing. Guest: Yeah, that's a tough one. There have been some economists, Steve Levitt among them, who have looked at that: if you think about it that way, what's the relationship between the growth in incarceration and the decline in crime. And certainly some of the decline in crime has to do with people not being on the streets. And how much--estimates vary. This is a case where it's a really tough empirical problem to solve. But there are a couple of things that are potentially going on there. One, you are potentially removing people who, let's think of as most at-risk, and removing them from the eligible pool. There have been demographic shifts over time. There are a number of other factors. But certainly there's some reason to believe that--there's reason to believe that this growth in incarceration has led to the decline in the crime rate. But that's not all of it. I don't think anyone would argue that that's all of it. Russ: The other part that you just alluded to is demographics. I've always believed, I thought I saw evidence to back it up but perhaps I was just confirming my bias, that the proportion of the population that's 18-24 and male has a huge impact on crime rates. But having said that, when you look at the growth--I think in your book starts in the 1980s--we're looking at, a lot of what I assume we are looking at is the availability of crack cocaine at a relatively low price. Which is, speaking as an economist, the technological improvement in people's ability to buy cocaine in small amounts, which has been, pardon the phrase, cracked down on rather dramatically by the criminal justice system. And that alone must explain a huge portion of that growth. Or am I exaggerating? Guest: A huge portion of the growth in incarceration? Russ:Yeah. Guest: Yeah, I think that there's no doubt that the crack epidemic, and the drug war more generally, is a huge explanation for the growth in incarceration. But I think one of the things that--scholars who study this historically really point to the Rockefeller drug laws in New York State and the criminal evasion of drug possession and sale and the custodial sentences that adhere to that as being one of the key drivers that led to the increase. And there are a couple of things that are really important that led to the--to keep in mind when we look at the role of drugs, drug policy, crack cocaine specifically, is that one of the things that we know--we know that kids are delinquent. Boys in particular are delinquent. And most young boys across racial groups, across socioeconomic status, different class groups, education levels, engage in some form of delinquent activity when they are young, in that age group exactly you are talking about--18 to 24, 16 to 24, or 18-30. And so when they are using drugs, selling drugs, they may engage in property crime, a range of other things. But one of the things we have done as a society is we've criminalized certain kinds of things differently than others. And this is one of the key explanations for why the growth in incarceration has affected certain socio-demographic groups differently. The evidence suggests that young white men and young black men use drugs at about the same rate. If anything, young whites may use drugs more. But they are much less likely to spend time in prison because of that. That largely has to do with where kids use drugs, where they sell drugs, and how we police. So, young African-American kids, kids of color, kids of low socio-economic status (SES), who maybe live in high-poverty, urban areas are much more likely to use and sell drugs in relatively public places. And that's exactly where you find greater levels of surveillance, more police presence, higher likelihood of getting caught. If caught, then they are prosecuted and ending up in prison or jail. So that's one key distinction why we continue to see such race differences and class differences in criminal justice context. Even though drug use--other survey data suggest isn't different across race groups. For example, among young men. And then another key thing, which is something I think states are thinking a lot about and how to remedy inequalities in sentencing, which is the very classic distinction between crack and powder cocaine. And so for the same amount of crack cocaine, sentences were typically much longer than for an equivalent amount of powder cocaine. And when we think about who was more likely, even going back into the late 1970s, early 1980s, who was more likely to use crack versus powder, African-Americans, those with low levels of education or living in impoverished neighborhoods were much more likely to be using crack than other young people. So we see these sentencing, the role of policing and prosecution and sentencing having these disparate impacts on different socio-demographic groups. |

| 29:37 | Russ: Let's talk about that for a minute, because a very occasional theme on this program is what Bruce Yandle calls the bootlegger and baptist explanation for public regulation. Which is that a lot of regulations are the strange coalition of people who have high-minded altruistic motives and those who have very self-interested motives. So there are a lot of people in America who don't like drug use, don't like other people using drugs, or for a variety of reasons think they are bad, so they support all kinds of rules about drug use, limitations on drug use, laws against it and sentencing for crimes that involve drugs. But then you have people with a direct, private self-interest in building prisons, like construction companies, prison guard unions, etc. And you alluded to that at some point in your book. So, I'd like you to talk about that and see if there's some way that might explain this distinction between crack and powder cocaine enforcement. Obviously, I think suburban white kids in rich neighborhoods and high education parents, they don't like their kids going to jail, and they have a lot of political power relative to kids coming from households that are very poor and where life is disjointed and education is low. So, we understand that. That's a reality that political power is not, even in the finest democracy, is not very equally distributed. But what about this bootlegger and baptist argument, that some people with economic interests have been pushing for this increased incarceration and sentencing? Do we have any evidence about that? Lobbying data, or contributions to politicians? Know anything about that? Guest: Yeah. I think the best evidence about that gets back to the state of California and the role of prison union guards--the prison guard unions, sorry. My colleague actually, who is now here at the U. of Washington, Katherine Beckett, has done wonderful work, and other people have done similar work in which they've looked at the economic and political interests of certain groups, and prison guards are one of them. Prison guards have an incredibly powerful union in the state of California. And although I've never seen it, I've heard it alluded to multiple times--apparently when you walk out of the State House in Sacramento, California, right there there's a memorial to prison guards, right at the entrance--or the exit; I guess when you are walking out you would walk right into it. And I think that speaks to the very powerful role that prison guards have played in the development and expansion of prisons, specifically in the state of California. I think this is also true in other places where there is an argument to be made that certainly there are private prison interests, in certain states, not in all states, that that's an opportunity for economic growth. And organizations that provide services to inmates, and that's a way in which they can benefit from increased growth. In the context of that--and in a time when, if you can recall back to the early 1980s and this idea that crack cocaine wasviewed as an epidemic, particularly in America's most disadvantaged communities, and there was this real concern about health and safety. In lots of ways there are these real concerns. They may have been overstated by the media, but even so that were driving sort of this more punitive philosophy. And even then and later and now. Where there's no one making the case on the other side. Which is: Okay, wait, what does this mean, this massive buildup, what consequences has it had for certain demographic groups? How is it being distributed? How is the risk of incarceration being distributed? What are the benefits to public safety, and how has the increased cost potentially outweighed the benefit, given the sort of large scale removal of certain subsets of the population, who arguably when they get out of prison or jail are worse off than they were when they went in? And we may individually say that that's fine, or we may think that that's punishment; but collectively, if we think about those subgroups of the population and those individuals in particular have needs; and if they are not able to work, not able to contribute to their families, not able to participate in the civic life of their communities, that we all be actually worse off than we were before. So the flip side is, on the one hand you have prison guards, prison operators, service providers and facilities who may be arguing for a more punitive approach; and people who are tough on crime--that's politically quite appealing I think to quite a lot of people. And when you have really nothing on the other side--no politician wants to be viewed as soft on crime. In environments where judges are elected, they don't want to be viewed as soft on crime. And so there's a real passivity on the other side, where: What does it really cost us? And I think this is a silver lining to the economic downturn of the first decade of the 2000s, in that states have really had to think hard about whether this is a good use of resources. Because they just don't have enough money.Russ: Yeah. You raised a lot of interesting issues. Just to take an example you don't hear very often--raising the minimum wage seems like a good thing. If it prices low-skilled labor out of the labor market, it encourages people it encourages people to find what we economists call the 'uncovered sector.' The places you can work that aren't subject to the minimum wage. And crime is one of those. We have a lousy education system in these areas, in poor areas of America, inner cities. And I agree with you that on an individual level, the system can be just. On an overall level the other forces that are working on these folks are ugly. No easy answer there. We'll turn later to a little bit maybe about what we could do about some of these issues. |

| 37:19 | Russ: Let's talk about sort of the heart of the book, which is the impact of the size of the prison population and its growth in particular on how we assess social data and social trends. Give us some examples of how we have misinterpreted data because we forget that there's an increasingly large number of people in jail. Guest: I think the key observation to begin with is that there's been this massive increase in incarceration. And 1 in 100 American adults is incarcerated, and I mean in custody, in Federal, state, local prisons or jails. So that represents 1 in 100 American adults. The risk of spending time in prison or jail is not equally distributed across the population. So, men are more likely to be in prison or jail than are women. African-Americans are more likely to be in prison or jail than are whites or Hispanics. And one of the key features of this growth over the last 35 or 40 years is that those with low levels of education are more likely to be in prison or jail. So, let me just give an example--and they are siphoned into prisons or jails and out of our view of sort of the American condition. And by that I mean that when we hear that the unemployment rate is, I believe, 7.7% right now, that data come from what's called the Current Population Survey (CPS). The CPS is a survey of 50-60,000 individuals who live in households. We've been collecting data just about the same way since the late 1930s when the survey was instituted, essentially to resolve disputes between the Hoover and Roosevelt Administrations over the depths of poverty and unemployment. We were going to do the Census in 1930; we were going to do the Census in 1940, but we didn't have a good sense in between of how high was the unemployment rate and how was it distributed across different subgroups of the population as well as geography. So we started doing this survey called the CPS; it was initially called the Sample Survey of Unemployment. It became the Current Population Survey in 1942. And that's the data that we use. We hear about it monthly when we hear about the unemployment rate. Among lots of other things. Now those data don't include the incarcerated population. Russ: And as you point out, they miss other people too. They miss homeless people, they miss military people often.Guest: Right. And I would argue that most of the people they miss, although this is an empirical question, most of the people that are systematically missed by that survey and others that are like it are more disadvantaged than the average American. And I use that term loosely. But the idea is, we've had this huge growth of incarceration, and it's siphoning the most disadvantaged segments of the population into prisons and jails and out of the view of surveys like the CPS. And so reasonable scholars, political analysts, a number of people have made really quite bold claims about progress among African Americans. And you can think about this in the context of we recently re-elected our first African-American President. And many people point to that as a real symbol of progress for African-Americans. And clearly there's been an increase in the black middle class and a range of other positive indicators. But people have used data from the CPS to make the claim that the high school dropout rate among young black men has declined. And it turns out that my research shows that if you include inmates, who are disproportionately high school dropouts, you see no improvement in the high school dropout rate, since the early 1990s. And no decline in the racial gap in the high school dropout rate. You also find that among young black men who have dropped out of high school, they are more likely to be in prison or jail than they are to be employed. Now we wouldn't see that if we just focus on those who are in the CPS. And then a third important finding, you know, people made the claim that the election of Barack Obama, America's first African-American President, was driven in no small part to record high turnout rates among African-Americans. And it's clear that the number of African-Americans who voted in 2008, and probably in 2012, although we don't know yet, probably broke records. But the fraction of the population, certainly among those with low levels of education, did not. And one of the primary explanations for that is because such a large fraction of young black men with low levels of education are in prison or jail, and they are excluded from voting--at least in 48 states--and evidence suggests that they don't vote in the others. And so the voter turnout rate among those most disadvantaged young black men was the same as it was--voter turnout, and by this I mean the fraction of the population that voted, not of eligible voters. The fraction of the population that voted was the same as it was in the 1980 Carter-Reagan election. Now that really challenges ideas of black progress, certainly in the age of Obama. Russ: Yeah. It's a fascinating, depressing set of factoids, which I think are basically true. I think. There are some challenges in interpreting them. Obviously you have to make some assumptions when you make those calculations. They are not totally straightforward. But your basic point is that if there's been a large rise in the proportion of the African-American population that is low-skilled, that is not visible to social science survey efforts, your measures of social science benchmarks are going to be distorted. I think that's undeniably true. It's not really a consolation, but I was going to say it's something of a consolation--low income people don't vote much anyway, as much as higher income people. But it's not like they don't vote. So obviously it makes a difference. It's an empirical question how important the magnitudes are. |

| 44:21 | Russ: I found the data on the dropout rate to be particularly interesting. And this is a general problem. I think the technical term is there is a concensoring[?]--you have a lot of zeros, people who aren't in the data or represented in the data as not doing something. So, for example, in regular economic data you have people who don't work. So, what's their wage rate? It is zero? Or is it what they produce that's not in labor market activity, on some kind of hourly basis? What we typically do is we exclude them. We do that because it's practical. We don't do it because it's the right thing to do. And the point you are making, which is dear to my heart as an economist, is when you are looking at averages, and particularly when you are looking at medians, if you are changing the left- or right-hand tail of the distribution systematically for reasons that have nothing to do with the phenomenon that you are looking at, you are going to get a very distorted view. And your work is an example of this phenomenon in a dramatic way. They're not in the data. Guest: Right. The primary insight in my book is an extremely simple one. Whether or not we agree on the assumptions we make about how we estimate levels of employment among inmates or what their education level is, or whether they would have voted if they could have is really a secondary point. I fully appreciate the concerns that people raise about that. When you think about what is the counterfactual, what would it look like if they weren't incarcerated, and I don't know actually. I've thought a little bit about that, but I think the primary observation is that when we are making claims over time and the sample we're observing over time is shifting in ways that affects those claims, that's deeply problematic. When we are making claims about the general population and we're systematically excluding certain subgroups, those who essentially make the picture look worse, then that's the problem that I'm observing. We categorically exclude certain subgroups of the population from these surveys, like the CPS. And many, many others. Those are related to health, those are related to family formation--just a wide range of surveys. And there have been different points in American history where we've missed certain subgroups. If you think about during WWII, we missed young men who were in active duty military. If you think about the late 1960s and early 1970s, also missing young men who were called up to active duty military. There are more people incarcerated now than there were in active duty military. And those who are incarcerated represent the most disadvantaged segments of the population. So we are excluding them. Now, how much difference does it make? That's where, this is something that I've tried to bring some data to bear on this in the book. But I recognize that people might dispute exactly how I've done that or question that. But one of the things that's really important to me as a sociologist who is interested in the study of inequality--I fully appreciate that if I were an employer and I were trying to set wages or if I were working for a state unemployment insurance department, I'd care what the unemployment rate is. I'd want to know how many people or what fraction of the population is unemployed but looking for work. Because that's a really good measure of slack, labor slack. If I work for a political campaign and I want to find and tap into veins of eligible voters, I'm very concerned about the voter turnout rate among eligible voters. But as a sociologist, I'm really interested in how we understand inequality and so it's as important to me to understand who is not working, sort of thinking about everyone who is unemployed and not working. Not just those who are still looking for work. And even for those who are incarcerated, who may be in some sense employed, but they are not covered by usual, conventional bargaining agreements or minimum wage regulations or anything for that matter. So from my perspective, it's more interesting to me to understand social inequality if we look at those people who are also excluded. Russ: Yeah, and as--the labor economist in me, in my old days as a labor economist, when I was a little more narrowly focused, one of the things that labor economists look at is time out of the labor force and its effect on your skill level. There's depreciation, obviously, for when people leave the labor force either voluntarily or involuntarily. And if you get arrested and you are spending a few years in jail, it's not so good for your wage rate when you come out. Not just because--even if there was no stigma. Even if you didn't have a problem not working for three years or making license plates, whatever you could do before if you were in the labor market obviously has decreased and your skill set is going to deteriorate a little bit. So that's another factor I had never thought about. |

| 50:14 | Russ: Let's talk about magnitudes for a minute. Now, 2.3 million people is a lot of people, but we're a big country. So, the way I took your data on the dropout rate, for example, is that if you look at the raw data without taking account of the effects you are discussing, it looks like there is improvement over time from the 1990s. That there's been a reduction in the dropout rate. And what your work shows, and as you say, obviously you can challenge it, but what you show is that it's actually flat. There's been no improvement. You could argue that's good news: at least it hasn't gotten worse. So, it's true it's not improving, but it's not getting worse, even if you include the invisible men that are in the title of your book. But just to give some general magnitudes, we have 2.3 million folks in prison or jail. What proportion of those are African-American, and what proportion of the total African-American population is that, so we can get a better idea of what the exclusion is that we are talking about? Guest: So, just over 90% of all inmates are male. Among male inmates, it's about 45%, 40, 45% are African-American. It varies a little bit depending on what type of facility you are looking at. And so what one of the key things that I look at is among young men, sort of we think of as the prime incarceration years, between the ages of about 20 and 35, that among young black men in that age group it's about 1 in 9 are incarcerated. So, 11% roughly. And then if we look at those with low levels of education-- Russ: I've got to stop you there. Because people get confused about percentages and they get confused about what's in the denominator and what's in the numerator. And whether you are talking about in the prison population or the general population. So let me give you my interpretation of that number. So, you are saying that if you took young African-American men, all of them in America, 11% of that population is in jail. Guest: Yeah. Russ: And what would the corresponding number be for young white American males?Guest: 1.8%. Russ: So it's 7 times higher, roughly. Guest: Yeah. Russ:That's pretty depressing. Guest: Yeah. And what we see--there was racial inequality. So, my book really charts changes from 1980 to 2008. That was really the last year in which data were available when I was working on the book. So, just for a point of comparison, in 1980 among that same age group of young black men, it was about 5%, 5.2% of civilian men were incarcerated. I basically exclude the military here. I'm not including the military. For white men it was just over half a percent--it was .6% of a percent. And then if we go to 2008, it's 11.4% for young African-Americans and 1.8% for young whites. Russ: So it's tripled for whites, and it has doubled for blacks. Is that correct? Guest: Yeah. More than doubled. Russ:A little more than doubled. Which is ironic given our earlier discussion. We're in the second or third derivative there, is the problem. But--they are high numbers. The trend is one thing, but the levels are very depressing.Guest: Yeah. The punchline, I mean the issue for me, is that among young black men who dropped out of high school, it's over 1/3--my estimate suggests 37% are incarcerated on any given day. So that's more than a third. Russ: Of high school dropouts. Guest: Of high school dropouts. So, if you think of what fraction of the total American population that is, that's relatively small. Russ: And it's shrinking. Guest: Well, my argument would say it's not shrinking. Russ: Yeah--I actually was thinking about a different comparison. I was thinking about college versus high school graduates. The proportion of Americans with a college degree has been growing, but unfortunately the proportion who are dropping out of high school can still be growing. Sorry. Guest: So if you think about that, more than one in three, according to my estimates, not to be too precise, 37%. And among whites it's 12%. So for young white men who don't finish high school, the incarceration rate is the same as it is or a little higher than for young African-American men, broadly speaking. And what that means--the point that I'm trying to make in my book--and I'm not always focused on the glass being half-empty, but I think if we really, if the idea is that we want to design social policy and evaluate social policy and do social science research to really understand what generates inequality, we can't exclude the most disadvantaged segments. Because there is really important information there. People make the claim about the school-to-prison pipeline--I think the evidence, whether or not it's the school to prison or exactly how it works is I think a great source of debate. But the evidence that there's a strong link between failing to complete high school and ending up in prison or jail is just overwhelming. Russ: And to take the monetary part of it, when people point out that not going to high school is an economic disadvantage and they look at ratios say of college graduate earnings or high school graduate earnings to dropout earnings, your work is suggesting that as bad as that is, it's worse if you include the people who aren't even in the data set, who are typically likely to have dropped out of high school, and then are in prison. Of course there's also the effect that--my earlier point--having been in prison, they've lowered their economic opportunities because their skills are depreciated; they have the stigma of being former prisoners and as a result, the high school dropout ratio is a mess. It has a lot going on there that needs to be disentangled when you are comparing wage rates of higher levels of education to high school dropouts. Because for that education class this is a very significant phenomenon. Which is eye-opening for me. |

| 58:03 | Russ: Do you want to say anything cheerful about what might be done to either "improve" this? Again, there's a tangled story here of personal responsibility and social policy. Are there changes in social policy that you wish were on the agenda that aren't, that might make things better? For me, that's improving the school system, getting rid of the minimum wage. But you, I'm sure, have different arguments, so I'd like to hear them.Guest: Well, I want to borrow some insights that have been introduced and championed by some very smart economists, like Alan Krueger and James Heckman. Looking at the criminal justice system in many ways as a product of, as much as it is a product of crime and criminal involvement, thinking about it as much as a product of the education system, particularly the K-12 system and even earlier. They and others have really made the argument that we really need to think about investing in early childhood education, K-12 education, exactly to prepare young people for a range of careers in a rapidly changing economy, and in many ways hopefully to avoid spending time in prison or jail, particularly for those nonviolent drug and property crimes. So I think that strikes me as one avenue. And I think it's something that people have increasingly talked about, particularly in the context of declining state budgets, where states, at the state level, are looking directly at these comparisons between K-12 education and criminal justice spending. And in many ways those dollars, they have to figure out how to allocate them. So I think seeing the growth of incarceration in its relationship to education is really important, and thinking about the kind of, what problems we are trying to solve with the criminal justice system. And I'm not sure that custodial sentences are the right way to go. I think there's lots of initiatives investing in education as a possibility; I think also these alternatives to sentencing, particularly in relation to drug offenses--drug treatment is a hugely important piece of the solution. And we know a lot more now than we did 35 years ago about the physiological bases of drug addiction and other things. So we know better, and it strikes me that we can design treatment that is more appropriate to the real problem. So, I don't know where we are going to go from here in the context of the 2.3 million incarcerated, but I think that there are some potentially positive avenues. And I also want to say that, I think directly related to my book, is that I think it's important for us as social scientists to pay attention to the tail of the distribution and try and find ways to incorporate that experience, whether it be through expanding the survey efforts or doing the kinds of things that I did which involves combining the different data from different sources, to sort of get a handle on what the processes are at work, not just about criminal justice context but also with respect to completing education or educational attainment, voter turnout--a whole range of different things. But I don't think we are going to get very far if we just ignore the most disadvantaged segments. |

No comments:

Post a Comment